The Domestic Building Dispute Resolution Process in Victoria

By Lovegrove & Cotton – Construction and Planning Lawyers

If an owner, builder or building practitioner are unable to resolve their disputes and differences there is a clear domestic dispute resolution pathway in Victoria. This article sets out generally the processes involved in two key Victorian dispute resolution theatres: Domestic Building Dispute Resolution Victoria (‘DBDRV’) and the Victorian Civil and Administrative Tribunal (‘VCAT’).

Step 1: Domestic Building Dispute Resolution Victoria (DBDRV)

Domestic Building Dispute Resolution Victoria is a free dispute resolution service provided by the Victorian government that owners, builders, architects and contractors can avail themselves of. The domestic building dispute must relate to domestic building work and will typically traverse issues to do with defects, contractual breaches, payment claims (i.e. money owed or money dispute) and delays. A useful lay definition of domestic building work can be found on the VBA website ‘domestic building work is work associated with the construction, renovation, improvement or maintenance of a home’.

The Process at DBDRV

There is a prescribed application form (that can be filled out on the DBDRV website) which has to be completed and submitted. You must have attempted to resolve the dispute directly with the other party prior to applying to DBDRV.

Once filed, a dispute resolution officer processes the application and decides whether the dispute comes within the jurisdiction of Domestic Building Dispute Resolution Victoria. If that decision is affirmative the matter will be referred to conciliation. Often assessors are appointed to investigate matters germane to the dispute, prior to tabling their findings to the parties.

A conciliator then convenes and presides over conciliation where the parties are encouraged to use best endeavours to settle the dispute. Prudence dictates the parties leverage off this opportunity to settle the case, essentially free of charge, because the longer the dispute ‘ferments’, the more intransigent positions become and the costs that are borne in the dispute resolution process start to play a part in the economics of the outcome. Furthermore, at this early juncture the parties have control over their affairs; such control wanes the further they venture into the dispute resolution vortex.

This innovation has much to commend it because it is a gateway to either settling the case through negotiation or a gateway to the more adversarial process in the Victorian Civil and Administrative Tribunal (‘VCAT’) absent settlement. Call it a ‘dispute triage system’, if you will. Prior to the establishment of the DBDRV, adversaries were compelled to issue legal proceedings in the VCAT and were not afforded an opportunity to mediate for some months. By that stage, thousands of dollars may have been expended. The DBDRV is a game-changer and an altruistic innovation on the part of the Government.

There will, however, be instances where disputes are so complex, the monies involved so large and the intransigence of one, or both, of the parties so pronounced that settlement will not be possible. In such a case, the conciliator determines that the matter is too complex to settle and will need to be referred to the VCAT.

If the matter is not resolved, the conciliator issues a certificate verifying that the matter was not resolved. If the parties are still intent on pursuing dispute resolution redress, the matter goes to the VCAT.

In summary, the process at DBDRV is:-

Step 1: Apply

Step 2: Jurisdiction check

Step 3: Initial assessment

Step 4: Prepare for conciliation

Step 5: Building assessment

Step 6: Conciliation

Step 7: Possible outcomes of conciliation

Step 2: The VCAT

Legal proceedings can be initiated in the VCAT if the dispute has gone through the DBDRV process and a resolution was not forthcoming. The www.vcat.vic.gov.au web site states that:

“if you have been to the DBDRV you must have one of the following to apply to VCAT:

- A certificate of Conciliation

- A rejection letter

- A confirmation of complaint letter from BACV

- A dispute resolution order

- A notice of breach of dispute resolution order”

For domestic building disputes, applications are made to the Building and Property List. There is a prescribed application form (accessible HERE) that is lucid and comprehensive in terms of the details that must be provided such as the:-

- Identity of parties;

- Amount in dispute; and

- Nature of claim and that which is in dispute.

Directions Hearing at VCAT

The VCAT will at first instance organise a Directions hearing which is exactly what the name suggests, it is an organisational, logistical and ‘next steps’ hearing where a Tribunal member presides over a forum to issue directions to all of the parties involved in the dispute. When a directions hearing is called the parties are notified by the Tribunal and they must attend.

At the directions hearing the parties, (be they lay or represented by their attorneys) will appear and an interlocutory and procedural time table will be set down. Typical orders are along the following lines:-

- A date for mediation will be set down;

- The applicant will prepare a statement of claim that will articulate the cause of action (typically this is prepared by a construction lawyer);

- The respondents will prepare a statement of defence or counterclaim;

- There may be an order where the applicant prepares a reply to counterclaim;

- There may be orders for discovery; and

- Where expert witnesses are used there may be an order that they be filed and exchanged.

There will be timelines set down for compliance with the above stages and events.

Mediation at VCAT

The tribunal appoints mediators to preside over and encourage settlement at mediation. Mediations are without prejudice to enable the parties to speak with candour without harbouring any fear that what they say or communicate will be held against them outside the ‘cloak’ of the mediation. The parties are required to prepare a position paper in advance of the mediation that will be submitted to the mediator and their adversary.

Participants are not required to engage lawyers but by and large do. It is common practice for the each party to engage an expert witness to investigate and diagnose the cause of a compromised construction outcome. A report has to be prepared in accordance with VCAT expert witness protocols and the prescribed form. It is common practice for the expert witness to attend the mediation. Absent the attendance of the expert witness, the attorneys in the main have regard to the expert witness findings in their submissions.

The mediator begins the mediation by announcing that he or she cannot compel settlement, and rather is there to assist the parties resolve their disputes and differences. The mediator will normally request that the applicant make the first submissions and the respondent will then be afforded the opportunity to reply with submissions in rebuttal.

There is an expectation that the parties will conduct themselves in a civilised fashion but sometimes emotions can run hot in which case the mediator will endeavour to cool things down and get matters on track.

Once the parties have presented their submissions the mediator convenes private and confidential caucuses in break out rooms, talks to the parties confidentially to determine whether there are any ways by which there can be movement to an accord.

After the parties have spoken in confidence to the mediator, the mediator will obtain permission to convey their point of view to the adversary either in person or by way of a reconvened forum. It is best to put aside a day for the mediation.

Mediations have their own rhythm and no negotiation is the same as another. Plaintiffs are desirous of achieving the best possible settlement which, in the main, translates into the largest amount of money to ensure that there is ample reserve for rectification whereas respondents tend not share plaintiffs’ expectations in this regard. This polarity lends itself to protracted negotiations and repeated offers and counter-offers. Mediation is sometimes referred to as win-win when there is a negotiated outcome abetted by the services of the mediator. Conversely, there is a view that mediation is about “lose the least – lose the least” as one of the hallmarks of mediation is compromise, and compromise involves concession which means that one is not motivated by all-out victory. Unless the parties are prepared to compromise it is unlikely that there will be a negotiated outcome.

In circumstances where an accord is engineered, terms of settlement are entered into and signed by the parties. The terms of settlement are binding and, once signed, the case is concluded. When the settlement terms are not adhered to, the aggrieved can get the matter reinstated in the VCAT by way of directions hearing.

If the matter does not settle, the mediator will conclude the mediation and the matter will be referred to another directions hearing.

At that directions hearing, further interlocutory orders will be handed down and there will typically be an order for comprehensive discovery of all documents germane to the dispute. Sometimes the matter is set down for hearing but prior to the hearing date there is normally an order that the parties must attend a compulsory conference.

Compulsory Conference

A compulsory conference (‘CC’) is very similar to a mediation save for the fact that the convener of the CC (typically be a member of the VCAT) will hear from both sides and will proffer an idea of how he or she things the case will go at trial. The convener, in the writer’s experience, will provide insight into some of the weakness and strengths, the ‘fault lines’ in the adversaries’ contentions and may well advise one of the parties in person, by way of private caucus that they are at risk of losing. The CC is a last-ditch attempt vehicle to have the case resolved before it goes to trial and is a great ADR innovation as it provides an inkling of the likely scenario at trial.

The Hearing

If the matter neither settles at mediation nor CC, the case will be set down for trial. The complexity of the case, the number of parties and the amount in dispute will determine the length of the trial and the allocation of the number of days. Typically, construction barristers are engaged along with instructing solicitors. Trials are expensive and the ability of the parties to have control over the dispute resolution outcome is diminished on account of the attendant risks that run with a matter proceeding to determination. The fact that both parties end up going to trial means that each party has sufficient attachment and investment in their own point of view that they are confident enough to run the case. Yet, it is that very ‘investment’ that generates the risk, for there will be always be winners and losers.

The parties will ordinarily rely heavily on expert witness evidence which will be subjected to vigorous cross-examination. The parties are, nevertheless, at liberty to parley and settle their cases at any time and this often occurs on the eve or trial or the first day, such is the fear of the costs of protracted trial and uncertainty of outcome. The longer the case runs, the more intransigent positions tend to become; such is the escalating burden of costs that accumulate day-by-day, week-upon-week.

If a hearing runs to conclusion it often takes many weeks before a decision is handed down. The decision is binding unless an appeal is filed within the statutory time frames.

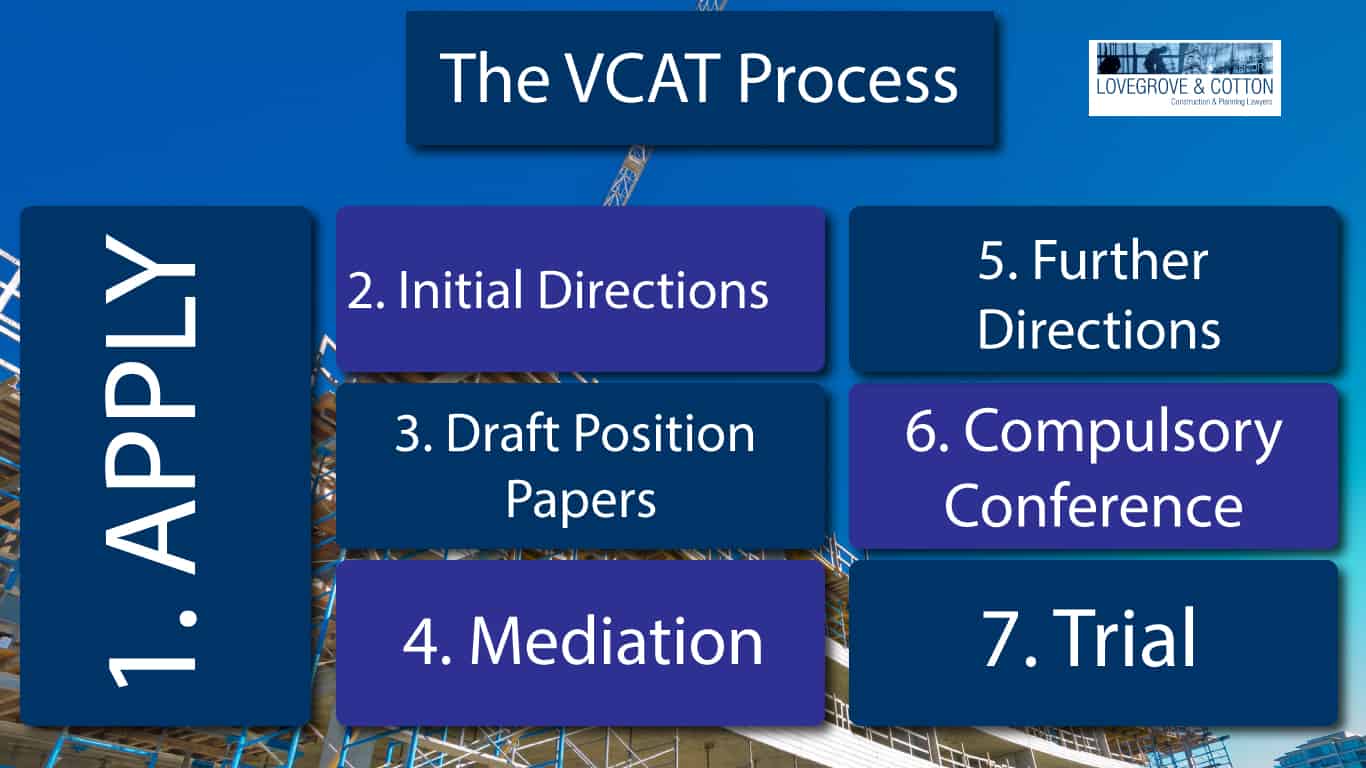

In summary the process at VCAT is:

Step 1: Apply to VCAT

Step 2: Attend initial Directions Hearing

Step 3: Prepare Position Papers for Mediation

Step 4: Attend Mediation

Step 5: If there is no settlement, attend further Directions Hearing

Step 6: Attend the Compulsory Conference

Step 7: If there is no settlement, attend Trial

If you are involved in a domestic building dispute and are unsure of what dispute resolution avenues you have, be sure to contact an experienced construction lawyer familiar with DBDRV and VCAT’s building and construction list.