The Guide to the BCA – No More Than a Guide

By Jarrod Gusta, Lovegrove & Cotton – Construction and Planning Lawyers

March 2014

In the construction industry in Australia it is common practice for individuals and companies alike to refer to the Guide to the Building Code of Australia (“the Guide”) to help interpret the meaning of provisions in the Building Code of Australia. The question this article raises is what is the legal status of the Guide when interpreting provisions of the BCA? Recent case law authority in the New South Wales Supreme Court and the Victorian Supreme Court, found that the Guide had no legal authority. By this the author means that an interpretation of a BCA provision that is based on the Guide is not legally correct, as the Guide holds no regulatory force. A BCA provision will be interpreted by a Court on the actual text of the provision and not the Guide’s explanation of the provision.

What is the BCA?

The Building Code of Australia is a document published by the Australian Building Codes Board. “The Australian Building Codes Board (ABCB) is a Council of Australian Government (COAG) standards writing body that is responsible for the National Construction Code (NCC) which comprises the Building Code of Australia (BCA) and the Plumbing Code of Australia (PCA).”[1] The Building Code of Australia is a document that is ‘called up’ by building and planning regulations in Australia. For example the BCA is defined in the Environmental Planning and Assessment Act 1979 (NSW)[2] and Reg 7 of the Environmental Planning and Regulation 2000 (NSW)[3]. It is likewise called up in the relevant Victorian Building Act 1993 and Building Regulations 2006[4]. The BCA prescribes set requirements and standards for certain types of building work.

What is the Guide?

The Guide is also a document published by the ABCB. The ABCB provides that the Guide is “To assist in interpreting the requirement of Volume One [of the BCA]”[5].

However the Guide states:

“The Guide to the Building Code of Australia (the Guide) is a companion manual to the Building Code of Australia 1996 (BCA). It is intended as a reference book for people seeking clarification, illustrations, or examples, of what are sometimes complex BCA provisions.

The two books should be read together. However, the comments in this Guide should not be taken to override the BCA. Unlike the BCA, which is adopted by legislation, this Guide is not called up into legislation (emphasis added by author). As its title suggests, it is for guidance only. Readers should note that State and Territories may have variations to BCA provisions. This Guide does not cover those variations. … The guide contains a number of examples – some written, others in diagram form – which help illustrate provisions. These examples are not absolute, as they cannot take into account every possible permutation of a building proposal. Again, they are intended as a guide only….

Because the Guide does not have regulatory force, neither the ABCB nor CCH Australia Limited accept any responsibility for its contents when applied to specific buildings or any liability which may result from its use…”[6]

Legal effect of the Guide

The key distinction between the BCA and the Guide is that the BCA is specifically referred to in Acts and Regulations where as the Guide is not. This is one of the key findings that Justice Lindsay made when interpreting the legal status of the Guide in the case of The Owners – Strata Plan No 69312 v Rockdale City Council (Rockdale City Case).[7] The Honourable Justice Lindsay found:

“The Guide adds nothing material to the language of the text of the BCA under consideration or, if it does … that addition is a gloss on the language of the BCA. The introductory paragraphs of the Guide expressly disclaim any pretence of the Guide rising higher than the text of the BCA.

At the end of the day, it is that text that must be construed. It is that text, not anything in the Guide, that was incorporated by reference in the Development Approval … It is that text, not anything in the Guide, that was the subject of “adoption and application” by regulations made under the Environmental Planning and Assessment Act, 1979.”[8]

The Rockdale City Case, concerned the interpretation of the meaning of effective height as defined in the BCA. The Guide did not merely add “nothing material” to the language of the BCA definition of effective height, it was “gloss on the language of the BCA”. This was the key danger or “red light” for anyone who used the Guide to interpret effective height under the BCA which the Defendants in the Rockdale City Case, found out to their detriment.

The BCA provided the following definition of effective height:

“the height to the floor of the topmost storey (excluding the topmost storey if it contains only heating, ventilating, lift or other equipment, water tanks or similar service units) from the floor of the lowest storey providing direct egress to a road or open space”[9]

The guide to the BCA provided:

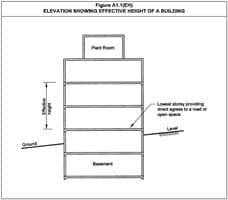

“Effective height measures the height of a building for safety purposes. Effective height is measured from the lowest storey providing direct egress to a road or open space (this will usually be the level at which the fire brigade would enter) – to the floor of the top storey. Plan rooms and spaces at the top of the building used for maintenance purposes are not included in effective height. See Figure A1.1(EH).”[10]

Figure A1.1(EH) was depicted in the Guide as follows:

The Defendants submitted that effective height, should thus be measured from the storey at which fire fighters would most likely enter the building which in this case was the pedestrian entrance. It was found however that the sub ground car parking storey was the lowest storey that provided direct egress to a road or open space. This misinterpretation of the BCA, could of in fact cost the Defendants’ a substantial sum of money as the difference in the height levels between the two storeys, meant that the building had an effective height of 26 meters rather than 25. The effective height of over 25 meters is critical of critical importance as fire safety requirements concerning the building become substantially more onerous once a building has an effective height over 25 meters.

Justice Lindsay stated further that:

“In that context, I formally rule that the Guide is not relevant to a determination of the proper construction of the definition of “effective height” in the BCA …. None of that material has evidentiary value, whatever use might be (and is) made of it as an aid to submissions.”[12]

The Rockdale City Council Case, is not alone in its treatment of the Guide. In the decision of Salter v Building Appeals Board & Ors [13], Justice Beach, held:

“It would, of course, be wrong to allow the draft discussion paper tendered (or indeed any other like document) to be used to alter the proper construction and application of the Building Code. To

do so would contravene basic and well known principles concerning the approach to be taken when construing documents of this kind. The same point may be made in respect of the guide.”[14]

Conclusion

The above cases demonstrate that the Guide to the BCA, holds no legal authority if it is not specifically called up by the Act or regulations. Practitioners must be very wary of using the Guide to help them understand the meaning of provisions in the BCA, as it CANNOT overrule any provision in the BCA, and cannot give a provision a meaning that is different from its plain English meaning. The author recommends the use of extreme caution when using the Guide to interpret the BCA, because if practitioners ‘get it wrong’ one may be liable to pay substantial sums of money in a negligence claim or potentially a defects claim. The most commercially prudent course of action if a Building Practitioner of Building Professional is concerned about the requirements of the BCA is to get a written legal opinion from a law firm that has expertise in this area on the proper interpretation of the relevant provision.

The “tom tom” drums in the building surveying fraternity have been beating and the tune of the beat revolves around the question, in light of the decisions, – “what exactly is the point of the Guide?” The above cases conclude that one cannot rely on the Guide in a Court of law to interpret provisions of the BCA. The Guide clearly states that it is a companion to the BCA and the two publications should be read together. However in the same introduction it states that it has no regulatory force and the ABCB will accept no responsibility for its contents as it is a guide only.

As an anecdote, I was talking about the Guide to a very senior construction lawyer the other day. He said and I quote: “I would exercise great caution in using the Guide to help interpret the BCA because absent it having any force of law its use as an interpretation instrument is potentially problematic”.

Insurance [2012] NSWSC 1244 at Para 43.

Aust Insurance [2012] NSWSC 1244.