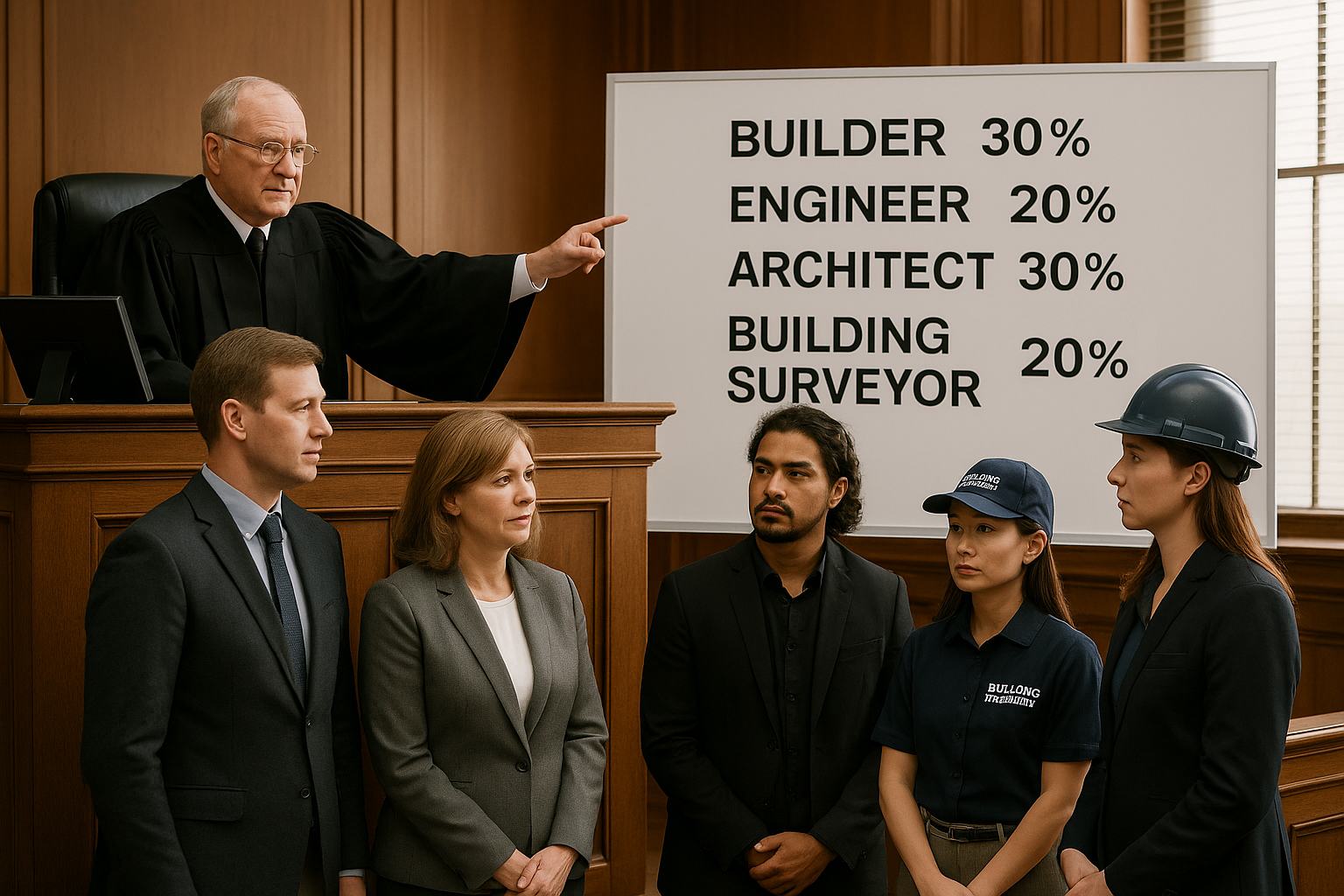

Colleagues, we meet at an historic juncture. On 18 August 2025, the Minister for Construction, Hon Chris Penk, announced from the Beehive: “It’s time to put the responsibility where it belongs. The Government will scrap the current framework, known as joint and several liability, and replace it with proportionate liability. Under this new model, each party will only be responsible for the share of work they carried out.”

That announcement marked the most consequential liability reform of New Zealand’s building-law landscape in a generation. For the first time, the entrenched doctrine of joint and several liability (JSL) will be displaced in building disputes, replaced by proportionate liability (PL).

Let us define these doctrines. Joint and Several Liability (JSL) – where multiple defendants are at fault, a plaintiff may recover the entire loss from any one of them, regardless of actual responsibility. That defendant must then seek contribution from others. In practice, solvent defendants – especially councils and insured professionals – shouldered residual loss.

Proportionate Liability (PL) – each party bears loss strictly in proportion to its fault. Ten per cent responsibility equals ten per cent liability; fifty per cent equals fifty per cent, period. The consequence is profound: councils and insured defendants will no longer be treated as insurers of last resort. They remain suable, but only for their corralled share of responsibility – not for overweight risk created by insolvent or primarily culpable actors.

My Role in the Law-Reform Journey

I speak to you not only as a New Zealand barrister and Australian construction lawyer, but as someone directly engaged in the reform process. In 2025, the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (MBIE) engaged our Australian firm, Lovegrove & Cotton Construction and Planning Lawyers, to advise on proportionate-liability pathways leading up to Cabinet’s decision.

My association with the doctrine stretches back 3 decades. In the early 1990s, as Project Director for the National Model Building Act, commissioned by the Federal and state governments of Australia, I helped design the first legislative framework introducing PL into the building sector.

Later, as Assistant Director of Building Control and instructing officer to Parliamentary Counsel, I pressed for compulsory professional-indemnity insurance for building practitioners. That advocacy help shape the first wave of reforms in Victoria and New South Wales.

To have contributed both at the doctrine’s inception in Australia and its adoption in New Zealand is professionally and personally significant.

Australia’s Two-Phase Story

Australia’s evolution unfolded in two phases.

Phase One

Early 1990s Building Sector – Victoria (1993): the Building Act introduced PL and mandated PI insurance for all key practitioners – builders, engineers, architects, designers, quantity surveyors, building inspectors and private surveyors – plus home-warranty cover for residential builders. The Northern Territory followed.

New South Wales in the late 1990s introduced PL and required insurance for residential builders and certifiers. Other jurisdictions adopted PL too, though not all implemented the same holistic insurance ecology.

Phase Two

Turn of the Century Insurance Hardening – When HIH collapsed and global PI markets tightened, cover availability became more challenging and expensive. Governments extended PL across the Australian economy to preserve insurance sustainability. It was not academic theory; it was pragmatic necessity.

In short, the 1990s reforms were driven by utilitarian risk-allocation in the building sector, and the 2000s expansion by insurance sustainability.

The New Zealand Context

New Zealand’s trigger was different: we did not experience an HIH-style collapse, but JSL produced similar distortions.

Under JSL, councils became defendants of last resort; builder and developer insolvencies left councils and insured professionals to bear residual loss.

Plaintiffs targeted the remaining solvent actors. Councils thus became de facto insurers of the system – regulators turned guarantors.

The idea of council’s having been, in a de facto sense, insurers of last resort, may once have been tolerable, but in today’s inflationary and risk-sensitive environment it is not sustainable.

It is this writer’s contention that Cabinet’s 2025 decision does indeed rebalance the system, in that it recalibrates tort liability and ascribes liability to those responsible to avoid overweight risk migration to local government.

The Philosophical Divide

At its core, this reform is philosophical.

Joint and several liability (JSL) enshrines plaintiff primacy – guaranteed recovery but distorted accountability and deep-pocket targeting.

Proportionate liability (PL) enshrines responsibility – liability tracks contribution and creates fairness and coherence by ensuring that fault and liability rest exclusively with the author of the wrongdoing.

PL is utilitarian and majoritarian, recognising the interests of citizens and ratepayers whose funds have long underwritten misallocated risk.

The contrast is captured by Murphy v Brentwood District Council [1991] 1 AC 398 and Invercargill City Council v Hamlin [1996] 1 NZLR 513. In Murphy, the House of Lords held councils owed no duty for pure economic loss.

In Hamlin, the Privy Council took the opposite view, finding councils liable on the basis that “until the defect was discovered or was so obvious that any reasonable house owner would have called in an expert to make investigations that, properly carried out, would have revealed the local authority’s breach of duty.”

That reasoning reflected New Zealand’s reliance on public inspection systems rather than any greater sentimental attachment to home ownership. An English homeowner would agree that the home is paramount, but not that a council should bear the loss — a distinction that defines Murphy’s individual-responsibility ethos.

PL now reconciles those philosophies, aligning liability with contribution while recognising the broader public interest.

Who Is the Consumer?

Plaintiff advocates often define “consumer” as the claimant alone – too narrow a lens as it does not tell the whole story.

Three constituencies share the system:

- plaintiffs

- citizens and ratepayers, and providers

- builders, architects, engineers, certifiers, and insurers.

True consumer protection embraces all three.

JSL favoured one; PL restores equilibrium for the majority.

Insurance – Myths and Realities

A persistent myth is that PL cannot function without compulsory PI. The Australian record says otherwise.

In Victoria, PI was compulsory for architects, builders, engineers, designers, surveyors and certifiers – an initiative I helped devise, promote and implement.

New South Wales in the 90s required it only for residential builders and certifiers, yet the system endured because most professionals carried voluntary cover.

Lessons: compulsory cover strengthens the system, but PL can operate without it where professional insurance culture is strong. Having said that I am a very strong advocate of mandated insurance and am well known to be so.

Hypothetical

Imagine a Christchurch façade failure where a builder is 40 per cent responsible, a structural engineer 30 per cent, and a consenting authority 30 per cent. Under PL, each pays that share – no one carries another’s insolvency.

Interface with Tort and Statutory Causes of Action

New Zealand’s transition will require careful alignment between PL and existing liability architecture – negligence, contract, and statutory duties.

Questions arise:

- Will PL extend to claims under the Fair-Trading Act 1986 for misleading or deceptive conduct?

- How will it interact with the Law Reform Act 1936 on contribution between tortfeasors?

- Will apportionment apply to duties under the Building Act 2004?

- New Zealand’s draft should mirror Court tested Australian legislative narrative wording to avoid uncertainty.

Legislative Process and Timeline

Following Cabinet’s August 2025 decision, MBIE has instructed the Parliamentary Counsel Office (PCO) to draft exposure provisions.

Promulgation likely in the first half of 2026. Transitional provisions will decide whether the new law applies to cases already filed – a critical point for litigators and insurers.

Reflection: Monitor the implementation critical path closely; filing timing may determine whether JSL or PL governs a case.

The IBQC Model and International Context

At the International Building Quality Centre (IBQC), which I chair, we assembled a drafting group including a former Chief Parliamentary Counsel, a Law Reform Commissioner and senior judges.

We produced a Model PL provision drawn from tested Australian statutes and submitted it to MBIE as a reference tool.

This model will also be embedded in the forthcoming International Model Building Act 2025, giving New Zealand a globally benchmarked template for consideration. The draft wording has been provided to MBIE for PC consideration.

The NZ Law Commission Perspective

NZ Law Commission has historically recommended retaining JSL, butdid so at a time when insurance markets were less challenged.

Two decades later, that landscape has changed: council payouts have risen, construction insolvencies have multiplied, and the policy balance has shifted toward responsibility-based allocation.

This shows the current reform is not reactionary but evolutionary – an evidence-based adjustment to modern risk realities.

Preparing for Transition

Post 2026 promulgation, lawyers will need to audit files and new instructions for potential apportionment issues.

- Insurers should update risk models.

- For engineers, architects and building surveyors, PL rewards precision, diligence and documentation.

- For councils, it reduces existential exposure.

- Homeowners should check the insurance profile of those with whom they contract.

- For ratepayers, it means public funds no longer subsidise others’ insolvency.

Conclusion – Responsibility-Based Justice

Let me return to the Minister’s phrase: “It’s time to put the responsibility where it belongs” Cabinet has adopted the responsibility-based doctrine.

Under JSL, councils and insured defendants were the insurers of last resort. Under PL, they remain accountable only for their share. Lacrosse proves PL works in practice and illustrates how it operates.

So let there be no misunderstanding: proportionate liability means each defendant is responsible only for the share of loss they caused – nothing more, nothing less.

This is responsibility-based justice – a utilitarian, majoritarian and doctrinally coherent model that aligns New Zealand with Australia and will reshape our construction law for decades to come. It marks a watershed moment in New Zealand legal history.

Author Biography

Adjunct Professor Kim Lovegrove DLitt, MSE, RML is a construction law reform expert and a New Zealand barrister with more than three decades of experience in building regulation and liability reform.

He served as project director of the National Model Building Act, contributed to the drafting of the Victorian Building Act 1993, and has advised governments, the World Bank, regulators, and industry in Australia, New Zealand, and internationally.

Professor Lovegrove is Chair of the International Building Quality Centre (IBQC) and the founder of Lovegrove & Cotton Construction and Planning Lawyers Australia, a boutique practice focusing on construction law, regulatory frameworks, and dispute resolution.

Footnotes

[1] ‘Why council liability reforms won’t save us from the perils of judicial lawmaking’, published in Law News authored by Roger Partridge on the 28 October 2025.

[2] The digital renders used in this article were developed collaboratively by Lovegrove & Cotton and ChatGPT. The photo images that are not the digital renders are stock images sourced from Shutterstock.