The Development of Best Practice Building Regulation – Key Take Outs and Learnings from 30 Years of Experience

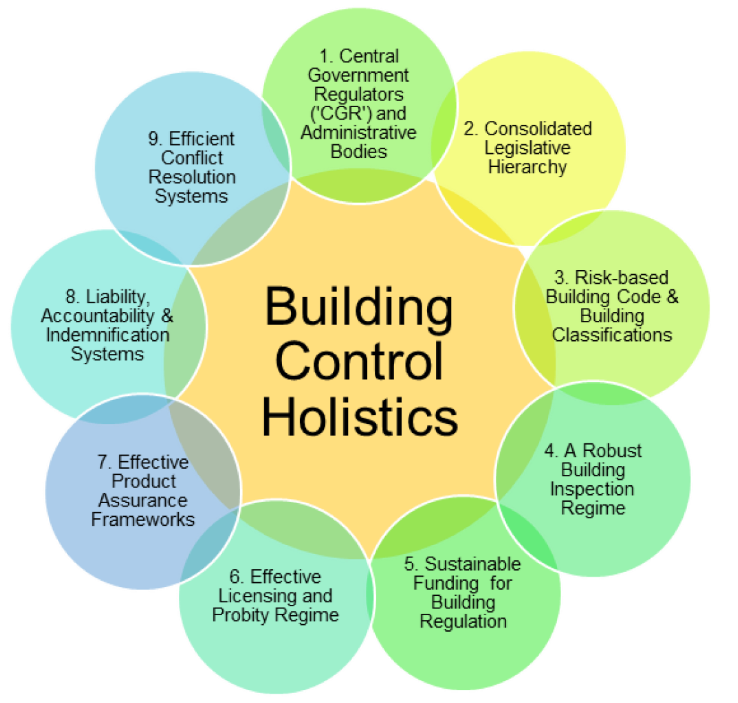

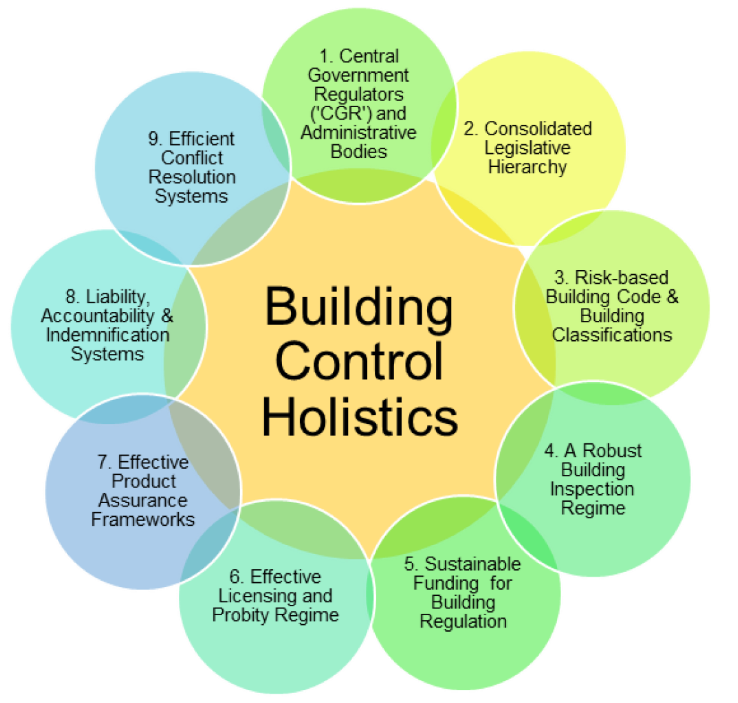

A holistic building control system will comprise all of the nine elements above.

I have had a number of building regulatory law reform deployments since the early nineties in the antipodes, Asia, and Africa.

That which has always captivated me has been international best practice approaches to the design of building regulation for the global citizen. The journey started in the early nineties when afforded carriage of the development of the National Model Building Act as the project director of the team.

The NMBA became the law reform blue print for Acts of parliament such as the Victorian Building Act 1993 and the Northern Territory Building Act 1993. It also introduced new concepts such as:-

- 10 year liability capping

- Proportionate liability

- Private certification

- Compulsory registration

- And broad church registration of key actors

Our team was given permission to study off shore jurisdictions to identify the very best in building regulatory constructs. The Australian liability system was very much British based, particularly with respect to liability limitation laws and liability apportionment.

That which transpired involved the adoption of some French based concepts in particular the 10-year liability capping and compulsory insurance of key actors to extrapolate the best law reform concepts. The exercise bore testimony to the merit in looking at far away lands, even different cultures, to extrapolate the best.

The French approach to liability and insurance is in this writers’ view, the best practice with respect to the most rigorous approach to final inspections of buildings, the joint inspection protocol for complex buildings which the Chinese have adopted has much to commend.

Subsequent deployments were off shore and included:-

- The participation in 2 law reform think tanks for the Japanese government in 2009 and 2012.

- World Bank law reform deployments in China and Malawi in the years 2019 to 2022.

- More recently and ongoing, is participation in the drafting of good practice guidelines for the development of building regulations with the IBQC.

In this paper I will extrapolate that which I consistently promote as being some of the best practice elements to date and continuing that make for enlightened building control. The recommendations are based upon a “cherry picking” of the best elements of that which I have seen in jurisdictional exemplars.

Best Practice Building Acts Comprise a Top Down, Bespoke and Dedicated Regulatory Hierarchy

Building Act – The overarching administrative provisions.

Building Regulations – The day to day operational provisions.

Building Code – The technical requirements.

There is one dedicated administrative hierarchy

A dedicated Minister.

A dedicated building department.

And a dedicated director or CEO that reports to the responsible minister.

The minister can have a shared portfolio but it is critical that s/he has exclusive responsibility over the building portfolio.

The department will be the central and vital organ of state that assumes overarching administration for building control.

The building regulatory system must be holistic

Like a Swiss watch, a best practice building system will comprise a number of essential cogs that interact with one another. Every cog is a vital and integral element in recognition of the fact that if one cog is missing the totality of the system is compromised and to varying degrees dysfunctional.

Building Permit Delivery Regime

A permit delivery regime that calibrates inspections with the building classification system under the building code. It will be illegal to carry out building work unless a building permit is issued.

There will be a dedicated statutory official responsible for:-

- Issuing building permits.

- Carrying out mandatory inspections.

- Issuing occupancy permits.

The mandatory inspection will calibrate with the codified risk profile in the building classification.

A risk based building codified classification system

The building code will comprise a classification system that classifies the types of buildings according to their risk profile.

Example

A low potential risk building classification will be:-

The likes of a typical warehouse, 4 walls, frame, one roof, concrete slab, uncontroversial use with reasonable space between the warehouse and the neighbouring building.

A high potential risk classification would be:-

- Multi unit residential high rise with more than 50 occupants.

- or by way of example a munitions plant, hospital, infectious diseases facility or penitentiary.

The building will marry the mandated number of inspections with the key risk junctures under the potential risk consequence classification.

In the case of higher risk classifications there will be a higher incidence of mandated inspections and peer reviews of highly qualified practitioners such as fire engineers and structural engineers.

The legislation will afford local government primary responsibility for the issue of building permits

Local government will comprise dedicated building departments that will:-

- Issue building permits.

- Carry out inspections.

- Issue occupancy permits.

- Issue enforcement orders for non-compliant building works.

- Prosecute those that break the law and fail to carry out work in accordance with the act.

All of the permit delivery functions will be fee for service and those that apply for permits and inspections will have to pay the council for the deployment of the building official to ensure that the costs of the department can be substantially underwritten by fee for service.

The official will not be able to issue a building permit unless satisfied that the plans are prepared by competent persons and are in accordance with the requirements of the code. The building official will not issue the occupancy permit unless the building work is fit for occupation.

Joint inspection protocol

At the final inspection the building official will arrange for a joint inspection that will comprise the builder, the architect, other principal actors such as the engineers to jointly inspect the site, check commissioning, ensure that the key actors are satisfied and have certified that the key risk elements of the building are operational and fit for purpose. It will be incumbent upon the practitioners to certify same. The building official will not issue an occupancy permit until the joint inspections have culminated in a state of affairs where the building is fit for purpose.

A broad scope building practitioner registration and licencing system

The Building Act will establish a broad scope building licensing regime to licence and accredit key actors.

Key registrants will Include at the very least the following actors:-

- Building officials/surveyors.

- Builders both residential and commercial.

- Building inspectors.

- Architects.

- Draftspersons.

- Building consultants that provide expert evidence in courts of law and tribunals.

- Engineers in the sub-categories of:

-Electrical.

-Mechanical.

-Civil.

The registration board will:-

- Set the registration and licencing criteria by way of bespoke qualifications and experience.

- Ensure that the registrants are insured.

- Oversight and manage practitioner conduct.

- Be empowered to investigate, discipline and expel recalcitrants.

Key actors will be required to be insured

Key actors will be required to carry insurance cover that is mandated by the Building Act. It will be illegal to hold out or carry out business as a building practitioner if uninsured.

10 year liability limitation period

The act will promulgate a ten year liability limitation period to engender certainty with respect to the commencement and conclusion of legal proceedings.

The ten year limitation period will begin to run from the date upon which the occupancy permit is issued by the building official

The ability to issue legal proceedings will expire 10 years hence.

Proportionate liability

- In circumstances where there are compromised construction outcomes by way of defective building works occasioned my negligence or poor building practices, litigation typically ensues.

- The Act will provide that any actor implicated in the generation of compromised construction outcomes will be liable for their own contribution. They will not be liable for the negligent acts, errors or omissions of negligent co-defendants or other implicated parties.

- By the same token they will be insured in accordance with the requirements of the act to ensure that plaintiffs have the reassurance of solvent defendants.

The above pie charts demonstrate the importance of insurance in a proportionate liability scheme; Each triangle is a party, making 2 scenarios of 5 parties each. The left circle shows how proportionate liability with insurance can better guarantee coverage to the plaintiff. On the right, one uninsured party (the missing triangle) illustrates where the claimant may miss out on recovery from that party if the respondent lacks the means to pay for the liability.

Effective building permit delivery dispute resolution

There will be an appeal mechanism under the act to allow parties affected by decisions of building officials to be appealed. Such decisions may be:-

- A failure to issue a building permit or occupancy permit.

- The challenging of a compliance notice.

- Or such other decision that is related to the building official’s exercise or lack of exercise of a statutory discretion.

- The decision makers will comprise one construction lawyer, a building official and another suitably qualified actor and they will be part time ministerial appointees.

Strong enforcement powers

The building department will be endowed with very strong compliance and enforcement powers.

The Act will give the department the power to:

- Issue emergency orders.

- Vacation orders.

- Initiate prosecution in a court of competent jurisdiction.

- Recommend licence suspension or cancelation to the registration body.

- Undertake random audits of all registered building practitioners.

Some related considerations

It doesn’t matter how good the Building Act is unless the government provides adequate funding for the system and the bureaucracy which funds this vital organ of state, the legislation will not be able to make good it’s statutory remit. The right type of resources are critical. Heads of department will ideally have qualifications and experience in the building sector so that they have an experience based affinity with the challenges of the sector.

To complement this, there will be a critical mass of policy, assessment, and enforcement operatives with skills and qualifications tailored to the demands and the “pathology” of the building industry.

In terms of enforcement, the enforcement regime must be in a word “powerful.” So much of the criticism that is levied at challenged bureaucracies is inadequate enforcement. It is the inability of the organ to respond in a timely and effective manner to complaints that tends to attract the ire of the consumer. But enforcement apparatus costs a lot of money so Treasury needs to commit the funds.

The building department is a vital organ of state and treasury needs to commit sufficient revenue to ensure that this organ operates most effectively.

There must be very strong and well thought through policy

In circumstances where there have been systemic failures, a large part of the blame can be levelled at inadequately thought through policy, be it economic rationalism, cutting the cost of the red tape at all costs, a free market – let the market “self-regulate” approach. There can be short term economic benefits with deregulation and a loosening of controls, but the long term consequences can be dire, both economically and socially . The “de-regulationary” approach that culminated in the leaky building syndrome in NZ case on point.

The most impressive approach to law reform that this writer has encountered was the Japanese approach. The government on 2 occasions when it was reforming it’s building standard law convened a group of international experts to think tank and advise on international practice approaches to law reform. They also were very much preoccupied with not only identifying best practice but also getting advice on what led to failure in some countries in order to inoculate themselves against things that could lead to failure down the track.

Maybe it is the age of the writer but a conservative disposition to law reform is better than an adventurous, the approach must be rigorous, discussion robust, the product of consultation with the very best of brains at hand.

This opinion piece is written by Adjunct Professor Kim Lovegrove MSE, RML and his views are those of his own and are not representative of any other body or party.

Disclaimer

This article is not legal advice and discusses it’s topic in only general terms. Should you be in need of legal advice, please contact a construction law firm.

There are other publications that are germane to this topic:

IBQC Good Practice Guidelines for Low Income Countries

Good Practice Building Inspector Guidelines for Emerging Economies

IBQC Principles for Good Practice Building Regulation