15 Core Elements of Best-Practice Building Regulation

Over the last twenty years, the effectiveness of building regulations has been tested in light of a litany of regulatory failures in a number of jurisdictions.

Some of the failures have occurred in advanced economies, economies that are not constrained by the extreme budgetary constraints of the developing nations. There has been a ‘pan jurisdictional’ or geographically indiscriminate footprint where nations from both hemispheres have experienced construction failures ranging from the significant to the extreme.

The leaky ‘condo’ crises in the nineties cost Canada many billions of dollars, as did the leaky building syndrome in New Zealand which has cost that country considerably more. The Latvian supermarket roof collapse which killed 54 people was a negative legacy of the GFC austerity measures and the dismantling of the national building inspectorate. Then there have been fire spread calamities such as the Brazilian night club 2013 inferno and Grenfell 2017, which claimed the lives of 242 and 72 lives respectively and more recently the Spanish fire that killed 10.

When viewed in aggregate, one could be forgiven for concluding that building control in many jurisdictions is not delivering as building failures in one form or another have assumed a serial dimension. So there needs to be a rethink and a redesign of that which can lay claim to being a sound building control framework.

Purists would consider that it would probably be best if the redesign of modern-day building control could occur in an ‘apolitical’ coalition of internationally venerated experts on enlightened building control, to ensure that critically independent lenses firstly diagnose that which is wrong with regulatory ecology and then secondly to divine the cure.

Fortunately there are some international thought leadership hubs, albeit not many, that are able to harness the requisite level of skill and objectivity.

One such body is the International Building Quality Centre (IBQC). Established in 2020 and launched by the Australian Governor General the Honourable David Hurley AC on the 4th February 2020, the IBQC has made significant strides in the development of best practice building regulatory guidelines. The guidelines are an ‘aide memoire’ to law reformers providing guidance on how to fashion building regulatory architecture.

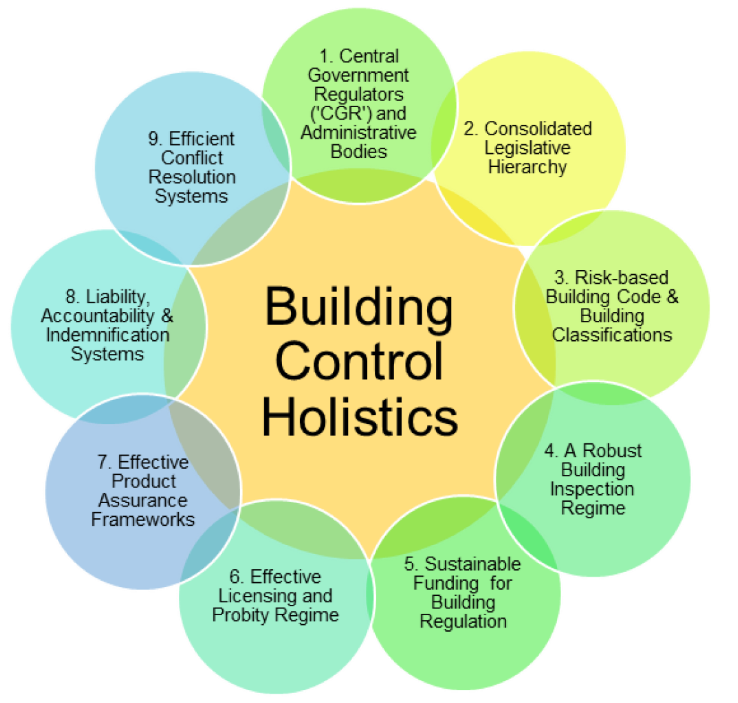

The writer submits that there are 15 Key Elements that make for good practice building regulatory ecology.

Having been deployed as a law reformer in a number of jurisdictions, the writer has been afforded the opportunity to identify best practice regulatory systems that are worthy of consideration for reforming jurisdictions.

1. There will be one Building Act

The Building Act will be called a Building Act and it will be the primary, holistic and overarching piece of legislation that will govern the regulation of building control in the state. It will be ‘mission control’, for all things involving building regulation.

The Building Act will be easy to locate, there will be no labyrinthine process involved in locating the legislation. One of the best ways of determining whether a governing act of parliament is readily accessible to the consumer, is to google a term like building act, if an internet search can immediately trace and reveal that act, then that is a good start. If one types in the word, building act and a potpourri of ill-defined regulations pop up, then that is a problem. The governing act of parliament will be easy to locate on the web, literally at one`s fingertip.

2. The Building Act will have Clear Objectives.

The objectives of the Building Act which will be called objectives will be clear and to the point. The Building Act 1993 Victoria section 4 is one such act that achieves this, and it does so with an economy of language. Section 4 reads as follows:

Objectives of Act

(1) The objectives of this Act are—

(a) to protect the safety and health of people who use buildings and places of public entertainment;

(b) to enhance the amenity of buildings;

(c) to promote plumbing practices which protect the safety and health of people and the integrity of water supply and waste water systems;

(d) to facilitate the adoption and efficient application of—

(i) national building standards; and

(ii) national plumbing standards;

(e) to facilitate the cost effective construction and maintenance of buildings and plumbing systems;

(f) to facilitate the construction of environmentally and energy efficient buildings;

(g) to aid the achievement of an efficient and competitive building and plumbing industry.

(2) It is the intention of Parliament that in the administration of this Act regard should be had to the objectives

set out in subsection (1).

3. There will be One Set of Building Regulations

There will be subordinate building regulations, called precisely that, ‘building regulations’. These regulations will be promulgated by the Building Act. They will deal with machinery or regulatory ‘drilled down’ and nuts and bolts matters like fines, timelines, penalties, prescribed fees and the like.

4. There will be One Building Code

There will be one Building Code which will enshrine the technical regulations and codified provisions that dictate how buildings will be built. The Code will be called the Building Code although it will also mention the name of the state e.g. the New Zealand Building Code.

In the case of a federal jurisdiction where there is a federal government, the code will be designed for national application, so that the local administrations can call up the Code, courtesy of the regulatory promulgation provisions in their local building act.

In the case of non-federal jurisdictions such as Singapore and New Zealand, there will be one National Building Act, one set of building regulations and one Building Code.

The codified building classification criteria will also have regard to the inherent or potential risks that are posed by different types of buildings such as:

Uncomplicated construction such as warehouses and storage facilities

- More complicated structures such as high rises

- Hospital facilities

- Residential abodes

- Civil defence facilities

Careful regard in the risk classification will be had to intended use, mindful of the fact that some buildings may harbour elements that in given scenarios can cause injury to people and environment. Warehouses that will house combustible or toxic chemicals would be case on point.

Rationale

From a consumer and industry perspective there are much greater efficiencies to be gained by centralised and single regulatory regimes. In jurisdictions where building regulations are dispersed in a number of statutes and multitudes of departments it is much harder for the user to navigate through the regulatory terrain. This in turn causes delays and a greater opportunity for misinterpretation, further it requires a greater diversified skill level, all of the above impact upon the optimum functional operationality of the building regulatory ecology.

It is not a stretch to realise that users are reassured if there is one act, one Code and one lead agency that administers building regulation.

The regulatory hierarchy and top-down approach where the technical code and building regulations are subordinate to the one act also make it clear which legislation and regulatory instruments assume precedence. When there is no clear hierarchy there is greater risk of conflict of laws.

5. There will be a dedicated Ministry of Construction

There will be a Ministry or a Department for Building Control. This lead agency will be the responsible body for overseeing the administration of building control in that state and will report to a minister that will be exclusively responsible for the building regulation portfolio in the state.

The ministry will maintain regulated interconnectivity with key departments like the Fire Brigade to ensure that regard is had to their policy recommendations, such is the importance of this instrumentality in terms of minimising loss of life to fire brigade personnel and the public.

Rationale

The logic in having one lead agency that performs the central administrative role for the building approval regime is compelling. The consumer will be in no doubt as regards whom the paramount regulatory body is and will not have to navigate between different lead agencies that interact or in some instances dint effectively in the regulatory ecology.

6. There will be a Practitioner Licensing Board

There will be a Practitioner Licensing Board which will license all building practitioners in the state. The board will come under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Construction.

7. There will be building officials responsible for the building approval process

The building officials will:

- Issue building permits

- Carry out building inspections

- Issue occupancy permits when the building is completed

Rationale

The rationale for the establishment of the dedicated discipline of building official, sometimes referred to as an accredited checker (Singapore) or an accredited certifier (Australian state of NSW) is that there is merit in the appointment of one designated person that is invested with the responsibility of overseeing the building approval, from commencement of the process to the end.

If multi-actors or agencies are engaged in this process then there can be significant delays to both permit issue, inspection and the issue of occupancy permits. Further the liabilities and accountabilities for oversight of the building approval process at law become opaquer and more diffuse.

There is much divergence of opinion internationally about the amount of power the official should have and the role of government vs a local government in the building approval process. Suffice to say opinion is mixed as some jurisdictions prefer to see the robust hand of the local governmental regulator rather than the migration of much of the approval task to the private sector.

Key determinants will be whether the oversight and regulatory probity regime is sufficiently robust to ensure that building officials are ‘disincentivised’ from compromising their statutory obligations for fear of attracting dire sanctions by the central regulator.

The building official will carry out at least 4 mandatory inspections at critical and legislatively mandated junctures and random inspections will also be required. Regard will be had to the IBQC risk based mandatory inspection protocols.

The official can either be an employee of local government or a private sector employee. If the official is a private sector employee that official will be audited on at least 2 occasions annually by a licensed government auditor who will ascertain whether the official has at all times discharged his or her statutory obligations. Japan by all accounts has maintained an annual mandatory auditing regime for private certifiers for over 20 years, very successfully.

The building official will ensure that, that which is approved and built, is carried out in accordance with the approved plans and the technical requirements of the building code.

8. There will be a final joint inspection

Prior to issuing the certificate of final inspection the building official will attend a joint inspection with representatives from the officers of all of the practitioners that have had paramount involvement with the building project. This will include the:

- Builder

- Design engineer

- Approving engineer

- Architect

- Any other inspectors

- A representative of the Fire Brigade/Department

The building official upon completion of the work will arrange the inspection and will be satisfied that the work is fit for occupation and will then issue an occupancy permit which will be filed with the local municipality. The joint inspection regime is very common in a great many Chinese jurisdictions and has much to commend it.

Rationale for the mandatory inspection regime and risk-based building classification codes.

One of the most vital parts of the building approval regime is the inspection protocol. A robust inspection regime operates like an early warning detector system, problematic construction scenarios are when they are future scenarios rather than as built outcomes.

Mandatory inspections at key junctures ensure that there is rigorous regard to each stage of construction so that the building official can if need be regularise matters, by issuing rectification notices and orders.

Absent mandatory inspections, there is no guarantee that any inspection will occur. Further absent mandatory inspection there exists a greater likelihood that compromised construction outcomes will not be discernible until a much later stage, on account of the fact that they were not identified earlier and at a time when the danger could have been thwarted.

The idea of a joint inspection which is an approach that is used to great effect in Shanghai, has compelling merit particularly for complicated and high-risk buildings. It affords the principal actors the opportunity to peer review in the presence of the official and determine whether indeed the building according to all, is fit for occupation.

Mandatory inspection regimes however are not universally in vogue. Some jurisdictions have ad-hoc inspection protocols, others allow for more self-certification and others have adopted a ‘one size fits’ all approach.

The one size fits all approach provides that regardless of the risk or consequence weighting of the building’s codified classification there will be the same number of mandatory inspection interventions.

- So an uncontroversial free standing four walled warehouse, with slab and roof, no sub-partitioning with a low consequence use and application, will by law require the same number of inspection interventions as an 80-story building or a hospital or elderly persons care facility.

- Before footing placement

The writer’s preference is that inspections be mandated by law. One jurisdiction that requires the carrying out of mandatory inspections is the Australian state of Victoria. The mandatory inspections stages are:

- Prior to pouring reinforced concrete

- Frame completion

- Inspection of fire inhibitors

- Final inspection

Although there is much to commend the Victorian Legislature for regulating the mandatory prescription of inspections, the limitation is that the inspection regime is not a sufficiently evolved risk base regime in that it is a ‘one size fits all approach’.

This inspection regime applies to all buildings regardless of their complexity or their risk ‘pathology’, be it simple and uncontroversial warehouse construction or SHR (super high rise). The Victorian Building Act 1993 fails to index the inspection regime with the inherent risk profile of the building classification and to that extent has limitations.

A best practice inspectorial regime would calibrate the number of prescribed inspections with the complexity of the intended building in use. It would follow that the ‘lower the mercury’ on the building risk barometer, the lesser number of prescribed inspections. It may follow that SHRs would require 10 inspections, warehouses 2.

Ideally a regulatory risk matrix would be developed by highly regarded technical experts with the complement of a very capable construction lawyer. The matrix would be divided into different building classifications and those classifications would then be matched with a regulated mandatory inspection regime.

The number of mandatory inspections and the type of inspections would be driven by construction complexity and the buildings` capacity to generate harm in circumstances where there are compromised construction outcomes.

A good illustration of a mandatory inspection protocol can be found in the IBQC 2024 guidelines, see the flow chart below.

Enforcement powers of the building official

If the building official observes any irregularity or construction input that is not in accordance with the building regulations then:

- A building enforcement notice will be issued

- If the notice is not complied with an order must be issued

- If the building official is from the private sector and there is noncompliance then the matter must be referred to an auditor at the Ministry.

The auditor will have powers to compel compliance. Furthermore, the auditor will automatically refer the matter of non-compliance to the Licensing Board for further investigation.

The auditor will be able to seek full cost recovery for any material noncompliance of an order issued by a building official.

Legislative provisions must be drafted to make it very clear that the building official affords no favours to owners or builders in respect of the impartial and decisive application of enforcement notices and orders.

As there is resort to private certification in some countries, strong probity controls are critical. The import of the provisions will be such that if an auditor or investigatory body establishes that a building official has not been impartial in the exercise of the enforcement powers, then that will be a ground for suspension of license and in circumstances where there is corruption or there has been evidence of financial incentivisation to turn a blind eye as it were then resort to criminal prosecution.

9. There will be a builder registration and licensing regime

The Ministry for Construction will establish the Licensing Board. The Board will determine the criteria for licensing and will oversee the probity regime for registration and licensing of practitioners to ensure that the public is protected from practitioner recalcitrance, professional misdemeanour and ethical compromise.

The Licensing Board will ensure that principal construction actors are licensed annually.

The criteria for gaining a practitioner license will be:

- An approved qualification

- Approved level of experience

- The maintenance of compliance insurance cover

- Maintaining annual compulsory professional development

- Payment of the annual licensing fee

The practitioners will be:

- Residential builders

- Commercial builders

- Engineers

- Building officials

- Building inspectors

- Architects

- Electricians

- Plumbers

- Proof engineers

- Designers and draftspersons

The Licensing Board will establish the qualifications and experience criteria for the actors. In the case of engineers, architects and building officials the qualification criteria will be not less than a degree in the respective discipline from a recognised university or tertiary institution.

With regards to the establishment of qualification criteria regard should be had to international best practice on point. The greater the skill, the level of professionalism and ethical propensity the less likelihood of optimum construction outcomes.

There will also be grading mechanisms. In Shanghai for instance to practice as a medium level engineer one must have a degree in engineering and 5 years’ experience. To become a quality assurance supervisor, the engineer has to obtain an additional 4 years’ experience and must then sit and pass a further examination to qualify as a quality assurance engineer. Under this system little is left to chance in terms of ensuring that a key actor in the building approval design and quality vetting process is up to speed.

In Germany the “proof engineer” is licensed by government to vet engineering designs and computations that have been prepared by the engineers and designers engaged by the developer.

This second set of eyes brings to bear the ‘lenses’ of total arm’s length objectivity and detachment along with a very high qualification and skill set. This approach resonates with a culture that is very much disposed to best practice quality outcomes.

The German approach has much to commend it with respect to complex buildings such as high rises or SHRs (super high rises), buildings that contain high risk elements or buildings that harbor the likes of combustible cladding; there is a lot to be said for making the deployment of a proof engineer mandatory by law.

10. Insurance

The insurability of a building regulatory environment is an insightful bellwether as regards whether a construction paradigm functions properly. The insurance industry keeps a very close eye on building regulatory failure and the pricing of construction risk.

Market underwriting is rather nomadic, insurers move in and out of markets as they are global players with global appetite and they don’t have an appetite for higher risk as countries that have experienced the flow on effect of the combustible cladding controversy have found out.

If insurers refuse to underwrite construction jurisdictions then there is little consumer protection for compromised construction outcomes so it is critical that regulation in light of its holistic and utilitarian make-up delivers an insurable paradigm.

An insurable paradigm will show case strong building controls, skilled practitioners and swift and efficient dispute resolution mechanisms and the most compelling evidence of building control success will be no construction related death and minimal claims for economic loss.

Building practitioners will be required by law to carry compulsory professional indemnity cover. This cover will provide indemnification for losses that emanate from negligent design or supervision. This assists the aggrieved in obtaining recompense for losses caused by building practitioners.

The insurance requirements will be approved by the Ministry and will be published in ministerial ordinances or gazettes and it will be illegal for building practitioners to practice unless they are insured.

In the case of builders, they will be required to carry a warranty cover that provides compensation for losses that emanate from defective workmanship.

11. Licensing Board Probity Regime

The Board will oversee the probity regime for the building industry in the state. The licensing body will have broad investigatory powers and will also have the power to:

- Conduct a hearing

- Fine suspend or cancel a license

- Refer heinous matters to the policy for criminal investigation and prosecution.

- There will be an investigatory and auditing arm of the Licensing Board.

Auditing

The auditing arm will ensure that all building officials are audited at least once a year. The auditing arm will ensure that all other building practitioners are audited at least once a year.

The auditors will be empowered to carry out random audits at any time. It will be incumbent upon the ‘auditees’ to afford full cooperation to the auditors with respect to giving the auditors access to building project records and practices.

The auditors will be required to have a technical qualification and a law enforcement qualification.

Rationale

Auditing and enforcement are critical in so far as it is one of the best means of public protection.

The Australian auditing regime that applies to lawyers that hold client monies in trust, ensures that audits occur annually. As the practitioner is ever mindful of the fact that he or she will be audited and investigated for errant practices, the process serves to put a break on any temptation to compromise a statutory obligation.

Funding of the Auditing Regime

There will be a user pays regime. The auditors will be accredited by the Ministry of Construction but the practitioners will pay the Ministry an amount that is commensurate with the auditor’s fee. The auditors need not be in the full time employ of the Ministry but will be accredited and approved by the minister and will at all times.

This auditing funding model regime would be based on the auditing regime for Australian lawyers (a user pays model where the lawyer is required to pay for the audit) that is established and has been pivotal in ensuring that practitioner recalcitrance is minimised. New Zealand also has had in place a like regime for many years.

Rationale

The rationale for the user pays auditing system is to ensure that regardless of the ebbs and flows of the building economy, the enforcement regime funding model is sustainable and not constrained by contracting governmental budgets. The Latvian supermarket roof floor collapse occurred as a result of post GFC austerity measures where the inspectorate regime was dismantled. A user pays self-funding auditing regime based on the Australian lawyer auditing model would ensure that this would never occur.

12. Emergency Powers

Where there is an imminent threat to life and limb or major adjoining property damage, the Ministry of Construction will be able to direct the building official to issue enforcement orders and directives immediately by also will maintain an absolute discretion to intervene on its own behalf and invoke whatever measures in its absolute discretion it considers necessary.

13. Appeal Powers Regarding Building Approval Matters

There will be a designated tribunal or division within that tribunal that will have the power to preside over and hear appeals in respect of the following:

- Notices and orders issued by building officials

- A failure on the part of an official to approve an inspection

- A failure on the part of an official to issue an occupancy permit

- A failure on the part of an official to issue a building permit

- The appealing of a reprimand or censure handed down by the licensing body

There will however be no appeal right in circumstances where the Ministry of Construction has been compelled to invoke emergency intervention powers.

There will also be a fast-track appeal procedure, where matters that require urgent determination are ‘moved up the line’. The Building Act will define the circumstances that qualify for urgent determination. There will be a significant fee levied for the initiation by the appellant of a fast-track appeal and this fee will be prescribed in the regulations.

Regardless of whether the hearing is a fast-track appeal or a normal hearing there will be 3 decision makers presiding over the appeal, one of whom will be a lawyer experienced in administrative or construction law.

The decision makers will be ministerial appointees and they will be chosen on account of them being venerated and respected by members of good repute from the construction fraternity. They need not be full time employees of the tribunal or the public service; rather they can also be employed in other capacities.

The members will be remunerated in accordance with a remuneration scale published in the regulations.

The Powers of the Decision Makers

The decision makers will have the power to:

- Uphold the decision of first instance

- Overturn the decision of first instance

- Award costs against the party that was unsuccessful

14. There will be Dedicated Divisions of Courts or Tribunals for Building Disputes

There will be dedicated specialist divisions of courts and or tribunals that will specialise in the resolution of building disputes. These specialist divisions will be established by legislation that will empower the designated theatre to have primary responsibility for the managing and resolution of construction disputes.

The jurisdiction will comprise mediators and specialist decision makers, be they judges or referees that facilitate the resolution of building disputes.

The regime will also ensure that in addition to providing accredited mediators there will be accredited expert witnesses whom are venerated by peers of good repute and these expert witnesses will be deployed to diagnose construction failure causation and the costs associated with rectification of same.

Both mediators and independent expert witnesses will be remunerated by the parties on a 50/50 basis to ensure that the costs are born equally. This will ensure that the state does not have to underwrite such deployment.

Judges and decision makers will be remunerated by the state and will be employees of the state judicial systems.

Rationale for Dispute Resolution System

Building disputes are complex and highly specialist and require the deployment and intervention of specialists with experience that is tailored to resolve building conflicts that are specific to this area.

Ideally the decision makers will have a background in construction law. In the Australian state of Victoria there are a number of dedicated construction dispute resolution theatres such as divisions within the Victorian Supreme Court and the Victorian Civil and Administrative Tribunal.

These divisions comprise decision makers that practiced construction law prior to their joining the bench.

Mediation will be compulsory on account of the fact that building disputes are very costly affairs. It follows that the sooner a matter is resolved, i.e. preferably at the genesis of the dispute, the less prejudice will be sustained by the disputants on account of “runaway” legal and expert witness fees.

The requirement for court appointed expert witnesses, is to remove the need for adversarial expert argument that tends to characterise plaintiff/respondent litigation. In terms of technical diagnosis there should be no argument, rather there should be clinical analysis of causes for building failure or compromised construction outcomes by one actor, in circumstances where that clinical analysis is:

- Independent and totally arm’s length of the parties rather than ‘expert for hire’ as it were

- Carried out by someone that is highly qualified and venerated by peers of good repute

- Remunerated in equal shares by the parties to ensure that the impartial deliberator does not need to be funded by the public purse

15. There will be a Fair and Clear Liability Regime

10 Year Liability Regimes

The aggrieved i.e. those negatively affected by a construction outcome that emanate from the negligence of a practitioner will have 10 years to initiate legal proceedings from the date upon which the occupancy permit was issued. 10 years after that period of time has concluded the plaintiff will forfeit the right to sue for damages. There will be one exclusion and that is where the negligence culminates in an injury or death, the claimant’s rights to sue will still remain intact.

Rationale

The system is based upon the Spinetta Law, a very established French liability regime that has underpinned French liability laws for many years. The concept has also been adopted by many Australian jurisdictions.

The rationale for adoption is that the limitation period is non-contentious as there is a clear and defined period for the initiation of legal proceedings i.e. 10 years, post issue of an occupancy permit. Furthermore, it is well established by insurance actuaries that by the tenth year, the incidence of claims emanating from a construction output dating back ten years prior, is nigh on non-existent; hence there is more than ample time within the ten years for the aggrieved to initiate legal proceeding as the defect that was consequential upon negligent construction would have revealed itself.

Proportionate Liability

This doctrine dictates that each practitioner that is responsible for his, her or its contribution to a construction failure will be found liable, for a percentage that is commensurate with or equal to the practitioner’s liability. When a number of practitioners are found liable for a negative construction outcome, the judge will apportion the liability between the defendants in the shares that the judge considers equate with their liability.

Rationale

Proportionate liability complements a compulsory registration and mandatory insurance regime in that all parties responsible, in their being licensed are also insured. This enables them to financially account for their failure. It is a fair doctrine in that accountability is measured and judged having regard to the allocation of contribution for construction failure.

The system was introduced to the Australian states and territories in the early nineties and has been well received by consumers and practitioners alike on account of its inherent fairness and jurisprudential logic.

Conclusion

It is considered that the best way for building control to move forward is for regulators to go back to the fundamentals, back to the drawing board. As building control is very much an in internationally interconnected paradigm in the 21st century, the pressure for regulatory harmonization is much greater not only within the context of local settings, be they federal or non-federal, but also ‘pan country’, ‘pan pacific’, ‘pan northern hemisphere’.

Best practice building control must be holistic, reminiscent of a jigsaw puzzle that can never be complete unless every component of the puzzle is incorporated into the complete picture. To leave out one piece of the puzzle provides a launching pad for harm down the track, which in the case of building regulation that can be fatal, literally. The completed picture must be designed to eliminate construction deaths, minimise negative economic impacts, and reach a balance of building efficiency with robust building control mechanisms.

Consistent with the globalisation of markets, products and systems is the need to develop internationally best practice building regulations that are inspired by precisely that, international best practice. A siloed look within approach to law reform is losing its cache, and in this writer’s opinion has little to commend it.

One of the reasons the emerging Asian economies are progressing so remarkable quickly is their willingness to be at the cutting edge, their willingness to be the best, to adapt and evolve. They are not held back by the inertia of the past or even the present for that matter.

Regulation has to be designed so that it can move forward in a progressive and utilitarian sense and regard should always be had to international best practice.

This piece is written by adjunct professor Kim Lovegrove, the chair of the IBQC. The writer has 3 decades in law reform, is a past senior law reform consultant to the World Bank and the founder of Lovegrove and Cotton Construction and Planning Lawyers. He is also a past Ethiopian Honorary Consul to Ethiopia and is the recipient of honours for humanitarian services to Ethiopia. Kim also still holds a legal practicing certificate in New Zealand.

Disclaimer

This article is not legal advice rather a discussion of the topic in only general terms. Should you be in

need of legal advice, please contact a construction law firm. Lovegrove & Cotton Lawyers and

our experienced team will assist you based on the facts and circumstances of your case.