There is now a “perfect storm” of financial challenges for domestic builders in Victoria, and no doubt elsewhere, and at the same time they are (for the most part) “incarcerated” by law with lump sum “fixed price” contracts.

Reasons for the challenges relate to post-COVID disrupted supply chains for materials, labour shortages, and interest rate levels affecting construction costs and new home starts.

Cost Plus Contracts Can Only be Used if Project More Than $1 Million.

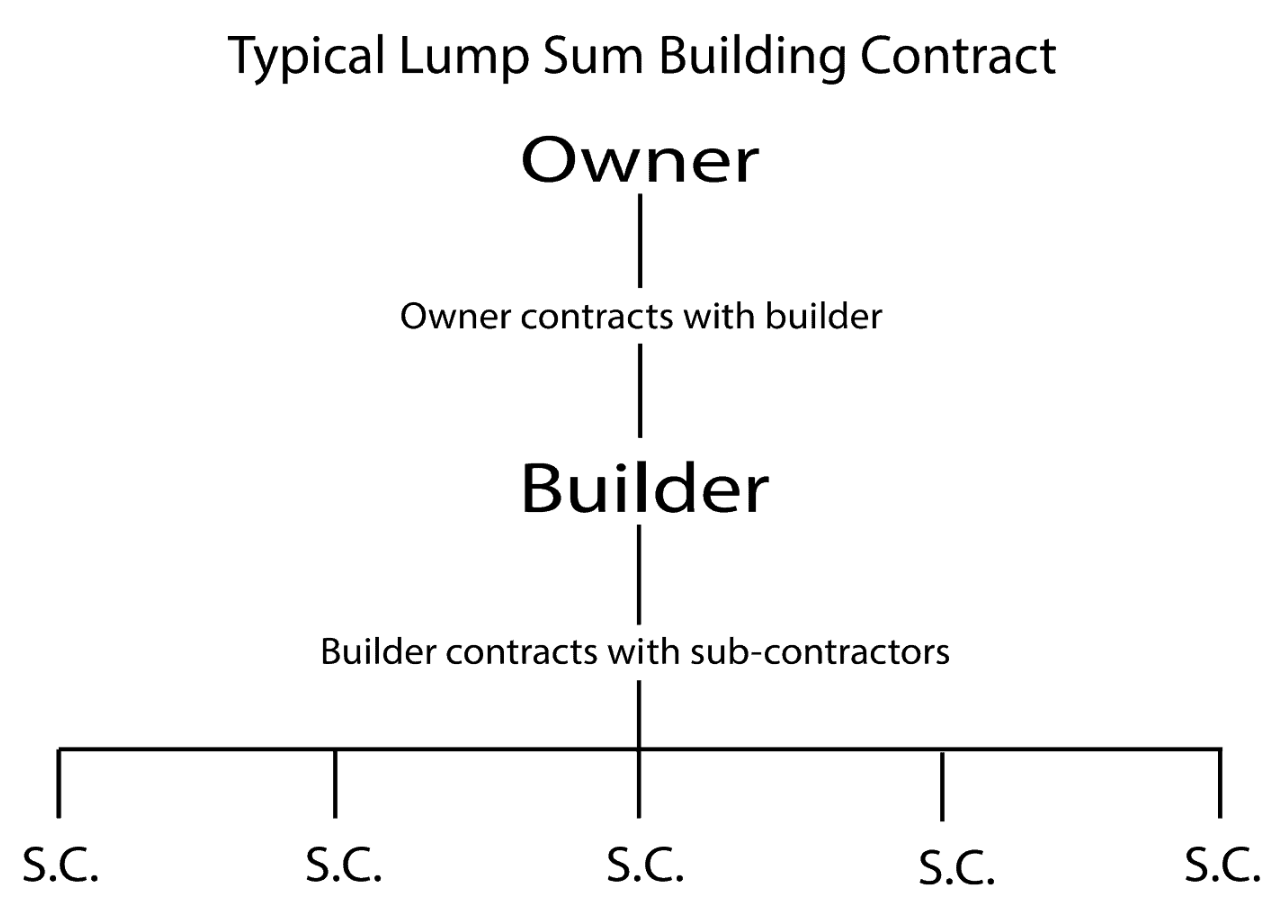

An exception to fixed price contracts would be where “cost plus” contracts are used, where the builder may charge whatever the cost of labour and materials actually is, plus a builder’s margin, on the understanding that invoices and receipts are produced when required to justify the cost. That said, cost-plus contracts can only be used in certain limited circumstances, for works valued at over $1 million. Often banks and lenders will not agree to an owner using a cost-plus contract.

(See clause 10 of the Domestic Building Contracts Regulations 2017, whereby the contract price threshold of $1 million was introduced, and see s13 of the Domestic Building Contracts Act 1995).

Back in the day before the Domestic Building Contacts Act was promulgated in Victoria in the mid 1990’s, standard industry residential building contracts had loss adjustment or rise and fall clauses. The purpose of these clauses was to allow for problematic price increase in labour and materials where such increases were well beyond the control of the builder.

Even some of the standard architect administered contracts had standard risk sharing clauses in the schedules where contractor and proprietor divvied up risk allocation on a percentage base for unforeseeable events or external intervening events.

It is submitted that if these types of contractual mechanisms were still in play, it would have stymied a lot of insolvency in the current paradigm.

Unless there is a sunsetting regulatory amendment that is introduced that provides for the resuscitation of a rise and fall mechanism, it is likely that insolvency activity will accelerate.

This could impact upon many building companies, which could become insolvent leaving:

- a significant number of unfinished building contracts and effected home owners.

- a series of subcontractors who are unpaid for services previously supplied.

- a rash of claims on domestic builder insurers, though the indemnity for incomplete works is corralled at only 20% of the original contract price.

- A rash of claims on the insurers will prove to be very challenging for the underwriters.

Once a builder has signed a fixed price contract with an owner, the contract price can only be increased during the works with the agreement of the owner if there are variations to the works, or if it is a situation where provisional sum or price cost estimates have been exceeded.

There are cases of builders trying to increase the overall contract price during the works, by adding a certain percentage or amount on top of the original contract price. However, if the owner does not agree to this increase, it is not possible to force the increase on owners. This is not a legitimate “variation”, which is about a “bricks and mortar” increase or change to the works scope, rather it is a unilateral price change that a builder requests an owner to agree to.

In some cases, an owner will actually agree to a negotiated price increase, as they know it will be an even worse outcome potentially if they need to change builders because an original contractor cannot financially afford to continue. Any new builder will add a significant mark-up to the price to complete and of course there will need to be a contractual variation signed by those parties in accordance with the Domestic Builders Contract Act.

Turbulent Times and Rough Seas

The causes for this vortex of “rough seas” for domestic builders are a series of factors that include:

- material shortages and delays, including from overseas, on a range of building products – the reasons include bush fires, post Covid disruption to supply chains, and even the war in Ukraine;

- labour shortages including in particular with subcontractors, meaning that projects are delayed, waiting on the necessary labour to be available, and the high demand impacts cost;

- there has been high demand for domestic building in Victoria due to the boost from the Home Builder Grant, however, builders have struggled to meet that demand;

- high interest rates have added costs for builders and is now dampening the level of new starts for domestic building contracts in 2023.

VCAT Delays

This is not assisted in Victoria by the delay in builders and owners being able to access prompt dispute resolution. For builders, this means that there is long delay in getting a determination from VCAT where payments under a contract are disputed.

There are long delays with the compulsory conciliation service (DBDRV). Then when the parties initiate action in VCAT there can be a delay of more than 2 years in getting the matter to final hearing, apparently due to a shortage of Members to preside on cases.

Builders have not unreasonably asked: Can I include a provision in new agreements with owners that allows an increase to the contract price if circumstances arise that were unforeseen when the agreement was formed?

Legislative Restrictions on Cost Escalation

Under the Domestic Building Contracts Act 1995 at section 15, there is a restriction on using “cost escalation” clauses in domestic building contracts. At subsection (2) it is specified that:

“A builder must not enter into a domestic building contract that contains a cost escalation clause unless-

- the contract price is more than $500,000 (or any higher amount fixed by the regulations); or

- the clause is in a form approved by the Director and complies with any relevant requirements set out in the regulations.” (Penalty: 100 penalty units).

There are moves afoot to have cost escalation clauses available for contracts where the original contract price is more than $500,000.

Subsection 15(3) of the DBCA states that a cost escalation clause in a domestic building contract is void unless, before the contract is signed, the builder gives the owner a notice in form approved by the Director (of Consumer Affairs Victoria) explaining the effect of the clause, and the owner has placed their signature or initials next to the clause.

The limitation here is that the contract price must be over $500,000, and not all contracts are for more than that sum, though many are. As well, Consumer Affairs has not yet approved the form of a notice to owners as contemplated by s15(3). Until that notice is available for use, cost escalation clauses will not be able to be used or relied on in new contracts.

It is suggested that this is a reform in need of urgent priority in Victoria, even if it is only for a sunset period where a period of time is allocated going forward to allow cost adjustment to apply until the macro settings improve. The solution contemplated in s15(3) is a start, and the form of a notice needs to be approved as soon as possible for use in new domestic building contracts.

For more advice and assistance on construction laws affecting domestic building practitioners in Victoria, do not hesitate to seek legal advice from lawyers with expertise in the field.

This is a Lovegrove and Cotton publication. Article written by Justin Cotton.

Disclaimer

This article is not legal advice and discusses it’s topic in only general terms. Should you be in need of legal advice, please contact a construction law firm. The experienced team at Lovegrove & Cotton can help property owners and building practitioners resolve any type of building dispute.