Some ways to strengthen the Drafting of Legislation in Emerging Economies

It has been said, albeit metaphorically, that the pen is mightier than the sword.1 It is hard to think of a mightier embodiment of the power of the pen than statute law as it provides the states` regulatory manifesto for the management of the affairs of society, the institutions, industry and the citizen. It is thus paramount that statute law is fit for purpose, regardless of whether it is in an advanced or emerging economy setting.

This cannot always be guaranteed, especially when the act’s drafters lack access to specialist legislative draftspersons- ie: specialists that have the skills to find the right words to give force to the policy aspirations of the legislature. The legislation (despite the best of intentions) may in material respects not be fit for purpose and therefore dysfunctional in certain aspects of its operation.

Many developed economies such as New Zealand, the United Kingdom and Australia to name a few, have dedicated governmental offices called Offices of Parliamentary Counsel2 comprising of lawyers (called parliamentary counsel) that specialise in the drafting of statute law. Parliamentary counsel are highly specialised exclusively in this area of the law and are ever mindful of it’s immense importance, as that which is enunciated in statute establishes the ground rules for the application of the rule of law. It binds the institutions and the citizen. It is thus critical for society that these specialist wordsmiths are so very highly skilled to ensure that the legislation is fit for purpose. Countries like the above are fortunate that they have dedicated offices comprised of these highly specialist lawyers that are most adept at crafting the language of legislation.

Due to economic constraints, some emerging economies may neither have offices of parliamentary counsel (‘PC’) nor access to their equivalents.

Some emerging economies do not have at their disposal civil servants possessing the required levels of specialist legislative drafting dexterity. The drafting of legislation is often not undertaken by those in possession of this highly specialist area of legal expertise. Rather, it is drafted by well-meaning civil servants who used best endeavours to put gravitas laden pen to paper. Absent the availability of lawyers in possession of such dexterity makes it often very hard to curate a suitably contextualised statutory narrative. If the narrative is not up to speed the Act of Parliament runs the risk of failing to make good it’s statutory remit, ie the codified culmination of the policy ambit and the law reform policies that provide the rationale for that remit.

Well-crafted legislation is akin to the intricate and seamless interaction of the many components of a fine swiss watch; a sum of all of the parts operating in unison to form a complete and perfectly functional instrument.

A best practice approach to the drafting of legislation will also involve a senior civil servant in the responsible ministry being appointed as an instructing officer to parliamentary counsel.

The instructing officer prepares a set of drafting instructions which can run into scores of pages. These drafting instructions are then provided to the parliamentary counsel appointed to draft the bill. The drafting instructions are an extrapolation and synthesis of law reform policy directives that are developed through extensive consultation over numerous months and sometimes years with many actors. (This writer is very familiar with the process as earlier in his career he assumed such a role).

The PC’s then prepare a draft bill. Often a number of drafts are prepared and refined. The instructing officer and the PC’s will ensure that the wording in the Bill encapsulates the policy imperatives that have been agreed upon before the Bill ultimately goes to Cabinet for approval.

As the paramount rule of statutory interpretation is the literal rule (ie to give the wording it’s literal and plain meaning) the wording of the act must be as ironclad as practicable. If the wording falls short, a judicial interpretation may not deliver that which was intended by the act. A somewhat “pyric cure” to this is legislative amendment which may or may not occur and if it does can take months or years.

Dickens once penned the ‘Law is ‘a’ Ass’ (Charles Dickens, Oliver Twist).3 In a metaphorical and contextualised sense, Charles Dickens may have been saying that the law does not work for all, possibly because it was not drafted cognisant of the social inequalities of that time. In our non-fictionalised world, the law is of course paramount as is the rule of law. The institutions that underpin and enforce the law are likewise paramount.

If there is a key takeout from the Dickensian metaphor, it may be that not all law is good law; however regardless of whether it is good law or bad law the citizen and the institutions are compelled to comply with it, as all are subordinate to the ‘rule of law’. Alas in some parts of the world history has been instructive in providing examples of regimes where the citizen has been bound by bad law with at times alarming consequences. Further if the rule of law is not operational, the consequences can be extreme and the term ‘failed state’ has been aptly named to describe such a worst-case scenario.

It is therefore better if the law promulgated has nothing within it that could be attributed to the Dickens euphemism. Hence the importance of dedicated offices such as Parliamentary Counsel, the virtue of which is to capture wording that is precisely reflective of policy intent and that which Cabinet ordained as it’s purpose.

In light of the resource constraints that exist in underfunded or fledgling democracies and the lack of aforementioned drafting expertise, there exists the risk that acts of parliament once proclaimed will promulgate laws that:-

- May be at odds with policy

- Generate unintended consequences

- May be unworkable

- May be unenforceable

- May repudiate reform intent

In an advanced economy setting, this is problematic enough when a jurisdiction is blanched with statute law that involves vexed elements. In an emerging economy the problem can be magnified with the risk that the law will be ignored or circumvented as economic constraints will prevent legal challenge or appeals to higher jurisdictions with the view to deriving jurisprudential remedy.

How to resolve this capacity constraint

There is a reluctance on the part of some Capacity Building Agencies (CBAs) such as NGOs and aid agencies, to actually fund the deployment of experts to draft the legislation that can complement capacity development where the expertise does not exist in the local bureaucracy.

This reluctance is underscored by the concern of some that liability might be visited upon the agencies that underwrite and facilitate policy reform even though the very same agencies may be pledging large sums of aid or capacitation capital. Said CBAs often provide large sums of funds, grants, loans, etc for state infrastructure. They therefore have an interest in the promulgation of ‘good law’ regulations that better protect the functionality and sustainability of the subject of the endowment.

This writer is not dismissive of the fear of liability, but wonders what the legal cause of action would be in circumstances where the CBE funds the deployment of ‘on-point’ law reform and legislative drafting expertise. If the fears were founded, legislation could incorporate statutory immunities that exonerate the CBE from any theoretical liability that may flow from problematic drafting. A condition of providing said funding could be that such immunity finds it’s way into an apposite act of parliament. This may however be an overreach if indeed the supposed liability is theoretical rather than real.

Alas if the CBA lacks preparedness to provide the legislative drafting expertise to a civil service that is without this expertise, there is a high risk that the statute will fail to deliver that which was envisaged. In other words it will not be fit for purpose.

It is the recommendation of this writer that when a CBA provides grants and state endowments for matters of state significance and has the ability to influence the utilitarian policy settings, that it also provides the experts that will work with the government to draft statute law that is fit for purpose. The costs of providing that resource would be miniscule relative to the size of many capacitation grants that can run into the hundreds of millions and the costs of getting the wording wrong in terms of impact upon the macro setting.

Within the context of building regulation, an area that the writer has a great deal of experience in, one of the consequences of an absence of specialised draftspersons is that there is sometimes confusion in some jurisdictions between the subject matter of an Act and a Building Code. It can overlap and contradict, this has the potential to make the legislation unworkable in key areas.

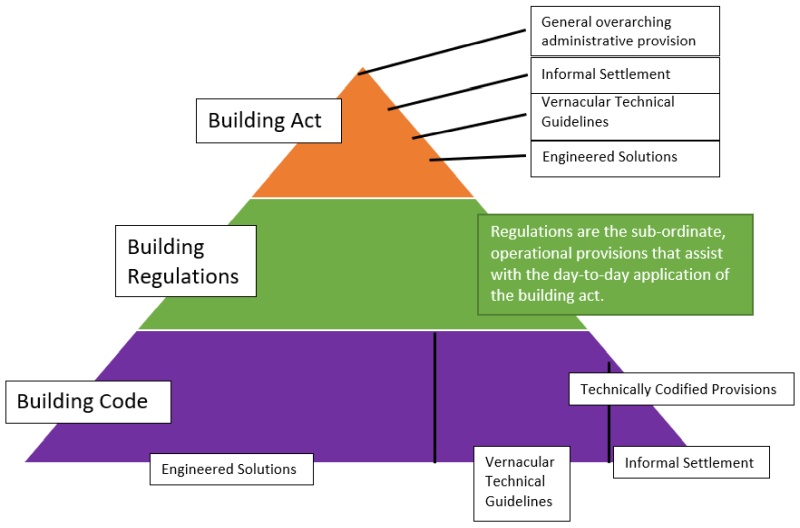

Good practice regulatory hierarchy will embrace a regulatory pyramid.

The building regulations will in top down fashion adhere to the below hierarchy:

1. Building Act

2. Building Regulations

3. Building Code

The Building Act

The Act will be comprised of the administrative provisions. It’s content will be along the following lines (albeit the list is not meant to be exhaustive). There will be:-

- The acts objectives

- Definitions of key terms

- The provisions that establish the key regulator and or regulators such as:

- The central government regulator

- Reference to the interacting other agencies

- The key offices, office holders, and the identification of the responsible minister

- The operational provisions

- Decision making powers

- Appeal rights and bodies

- Powers to promulgate regulations, ministerial orders and the like

- Funding mechanisms

- The powers to promulgate and call up subordinate instruments such as building codes and Ministerial orders

Building Regulations

The Building Regulations are subordinate to and correlated with sections in the overarching act of parliament. For instance, the act might state that all building practitioners must be “qualified and experienced” while the regulations stipulate the qualification and experience criteria. The act will have mechanisms to empower any necessary amendments to the building regulations and the required amendment methods.

Best practice will dictate that the Act will be drafted by parliamentary counsel and if there is no such counsel, lawyers that have experience in regulatory drafting will be found and deployed. It is emphasised that they must be lawyers. One does not go to a mechanic for heart surgery; equally one is ill-advised to deploy a non-specialised lawyer to pen the law of the land.

The Building Code

The Code will be called up by an enabling power in the Act.

The building code is not an administrative instrument as it concerns itself with technical matters and standardisation such as:-

- Heights

- Widths

- Material composition

- Formulas

- Prescribed technical criteria

- Good practice standards

- Building classifications

- And so forth

Best practice will dictate that the codified provisions are drafted by those with applicable technical qualifications and experience. This will involve directions from construction lawyers to better ensure the resulting acts and codes reflect the technical meanings intended by drafters when interpreted in a court of law. This requires tailored legal dexterity as the courts and the tribunals are the interpretative agencies, even though assisted by technically qualified expert witnesses.

There will be no confusion or fusion with respect to the contents of the act or code. The act is an instrument which is administrative and overarching while the code is exclusively technical. This may seem self-evident and obvious but avoidance of these misunderstandings is not always attained; the writer has seen instances where the demarcation between code and act is:-

- Duplicative

- Not demarcated effectively

- Contradictory

Hence in material respects unworkable.

The Composition of the Ideal Regulatory Drafting Team

Best practice will ensure that:-

- There is a legislative drafting project manager accompanied by:

- Research and development experts

- A legally qualified draftsperson with specialist skills

- A consultative mechanism to ensure that the project manager can formulate policy with key stakeholders

- A construction economist

- Ideally there will also be an economist that can be bring to bear expertise on the cost of regulatory impact. ‘Back in the day’ it was standard practice for a construction economist to prepare regulatory impact statements that assessed the cost implications of law reform. The writer recalls some reforms being thwarted as it was identified that the cost of implementing them would be too onerous for consumers and industry actors. Good law as stated above cannot be beyond the of reach of ‘main street’.

- Finally, the team will work closely with the host bureaucracy, the funding NGO, and the key stakeholders to ensure that the law is contextualised to the local jurisdiction.

Key Take-outs

Good policy and law reform will not be delivered unless it finds it’s way into well drafted and fit for purpose legislation. If the local jurisdiction does not have at its disposal parliamentary counsel endowed with the skill sets referred to above, then it is this writer`s contention that such dexterity would be very usefully accessed through other avenues; be they off shore lawyers or legal consultants experienced in the design of legislation and the drafting of its narrative.

NGOS that are pledging resources and funds for law reform and state capacitation initiatives that require policy codification and promulgation are encouraged to be live to this issue, notwithstanding that as stated above there is a view that a theoretical liability may apply to the provision of such resource. Policy sustainability depends upon it’s incorporation into the legislation and application and enforcement of that policy by a viable and sustainable civil service.

Whether the pen is mightier than the sword is moot and a debate on the efficacy of this saying is beyond the scope of this paper. But there can be no doubt that the wording of the law is of immense importance and if the appropriate level of drafting dexterity is beyond the reach of an emerging economy or any economy for that matter, then it is in this writer’s opinion, for fear of laboring the point, of utmost importance that it is made available, for the consequences of such neglect can be dire, if the upshot is that legislation is not fit for purpose.

The writer Adjunct Professor Kim Lovegrove MSE RML

The writer worked closely on the development of the Building Act 1993 for a period when he was assistant director of building control. He has also instructed the officer to Parliamentary Counsel in the Australian state of Victoria.

When he headed up the team that facilitated the development of the National Model Building Act, (NMBA) he on behalf of the Australian Uniform Building Regulatory Coordinating Council (the predecessor of the ABCB) worked closely with the New South Wales parliamentary counsel. The culmination of this project was the publication of the National Model Building Act which became the law reform template for overhauling building control in a number of Australian jurisdictions such as the Australian state/jurisdictions of Victoria and the Northern Territory.

The Model Act enshrined the policy aspirations of law reform that took the law reform team 12 months to develop. The writer can attest to the fact that the key law reform maxims found accurate expression in the finished product, a National Model Act. The NMBA was fit for purpose and was destined to be a very persuasive law reform instrument in modern day building control in various Australian jurisdictions as the NMBA provided the law reform blueprint for:

- The first ever proportionate liability provisions in Australia

- 10 year liability capping

- Registration of key building practitioners

- Consolidated and top down legislative hierarchy

- Expedited and cost effective appeal mechanisms for building permitting matters

In the above law reform capacity the writer gained insights into what he would describe as best practice legislative drafting. Insights that have proved sustainable.

A special thanks and acknowledgement goes out to Dennis Murphy QC who headed up the Offices of NSW Parliamentary Counsel, the offices that drafted the National Model Building Act.

Disclaimer

Disclaimer

This article is not legal advice and discusses it’s topic in only general terms. Should you be in need of legal advice, please contact a construction law firm. The experienced team at Lovegrove & Cotton can help property owners and building practitioners resolve any type of building dispute.

References:

1. Edward Bulwer-Lytton, Richelieu; Or the Conspiracy: A Play in Five Acts second ed), London (1839), p 39.

2. Policy to Law, Parliamentary Counsel Office, New Zealand Government (Governmental Website, accessed 21/12/2022) <https://policy-to-law.pco.govt.nz/>.

3. If the law supposes that said Mr Bumble ..”the law is a ass a idiot. If that’s the eye of the law, the law is a bachelor; and the worst I wish of the law is that his eye may be opened by experience – by experience.”

Charles Dickens; Oliver Twist chapter 51 489 (1970) first published serially 1837 -1839).