Some Musings on Reform Ideas for the New Zealand Building Regulatory Framework

Introduction

These reflections outline several ideas on ways by which the New Zealand building act can be reformed, the ideas are for the consideration of policy makers. Many of the suggestions below are in keeping with the IBQC Principles for Good Practice Building Regulation.

1 Practitioner Registration System

- Expand the registration system to include engineers, builders, building surveyors, and architects.

- Develop legislative criteria for registration that mandates specific qualifications.

- Introduce a regulatory mechanism to register building practitioners capable of obtaining professional indemnity cover.

- For residential builders, if there is a desire to introduce mandatory insurance cover, consider implementing a warranty cover similar to the systems in Victoria and New South Wales, Australia. Reason being both jurisdictions have had in place a viable insurance regime for many years.

2 Apportioning Liability to Reduce Financial Burden on Local Government

- Introduce a regulation to apportion liability to reduce financial pressure on local governments involved in legal proceedings.

- Ensure no respondent is liable for more than their judicially determined share of responsibility.

3 Mandatory Insurance Cover for Building Practitioners

- Introduce mandatory insurance cover for key building practitioners as a prerequisite for registration.

- Consider the Victorian model, where key actors in the construction process must be insured to improve consumer protection.

- Implement a combination of proportionate liability and mandatory insurance to ensure comprehensive coverage and enhanced consumer protection.

4 Risk-Based Building Classification System

- Introduce a Risk-Based Building Classification System into the New Zealand Building Code, aligned with the IBQC guidelines.

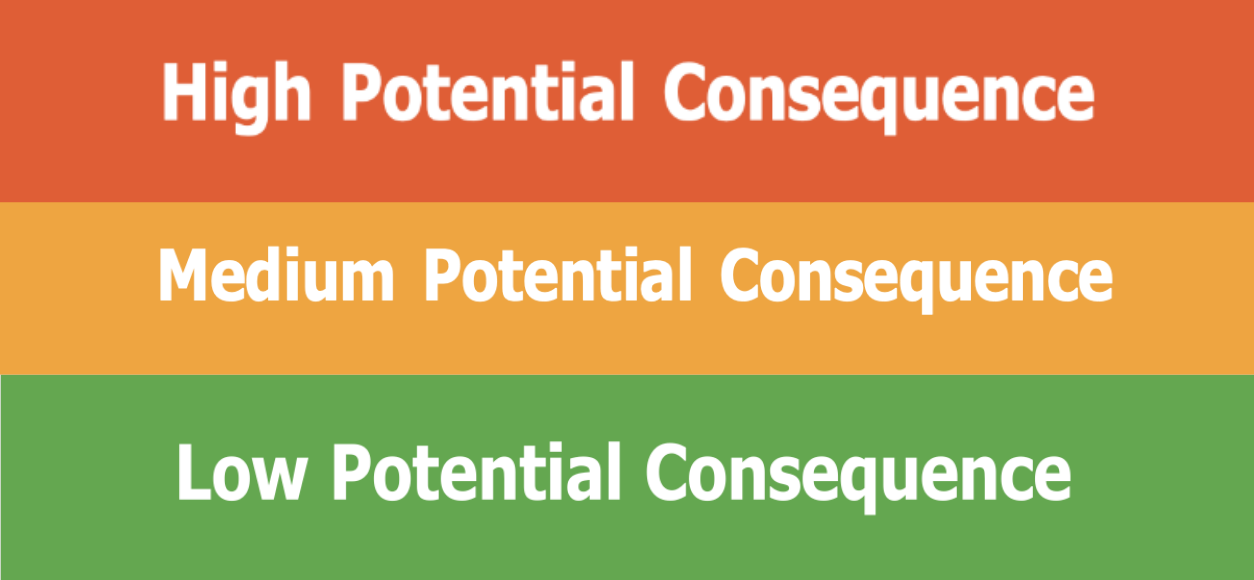

- The system should include three categories of potential consequence:

Image Credit: IBQC

- Low Potential Consequence: Buildings with minimal risk to life and property if failure occurs.

- Medium Potential Consequence: Buildings with moderate risk to life or property.

- High Potential Consequence: Buildings where failure could result in significant loss of life or property damage.

- This classification system will enable regulators to prioritize resources and inspection rigor based on risk levels.

- For more details, refer to the IBQC Risk-Based Building Classification Guidelines.

5 Mandatory Inspections at Key Stages

- Introduce mandatory inspections at key stages of the building permit process.

- Ensure inspections are conducted by building officials employed by a consent authority.

- Require builders or property owners to notify officials when a stage is completed.

- The system should culminate in the issuance of an occupancy permit by the official.

6 Clear Liability Limitation Periods

- Establish clear limitation periods with a defined start date.

- The 10-year limitation period should begin when the occupancy permit is issued by a building official.

- File a copy of the occupancy permit online with a government agency for perpetual access.

- Make the document publicly available so that potential owners, successors in title can easily access it to know when the limitation period concludes.

7 Risk-Based Approach to Building Inspections and Classification

- Introduce a risk-based approach to building inspections and classification, in line with IBQC’s guidelines.

- Focus a higher concentration of mandatory peer reviewed inspections on higher-risk classifications, while lower-risk buildings, such as warehouses, would have a calibrated inspection regime.

- This approach would reduce unnecessary regulatory burdens for low-risk buildings whilst better allocating finite inspector resources to high-risk classifications.

8 Final Joint Inspection Protocol

- When the writer served as a senior law reform consultant to the World Bank, the advisory team visited China on multiple occasions to provide insight into world’s best practices for building permit delivery.

- One exemplary system observed by the writer was the Chinese Final Joint Inspection Protocol. In this protocol, once a building was completed, a council building official would call for a final joint inspection.

- This inspection involved key parties, including but not limited to:

- The property owner

- The builder

- The principal architect

- The quality assurance engineer

- Together, these parties would attend the final inspection and conduct a peer review inspection of the completed construction.

- In some cases, the initial inspection would identify areas requiring further attention, necessitating additional inspections.

- Ultimately, when all parties were satisfied that the construction outcomes were fit for purpose, the building official would sign off on the project.

- In the writer’s view, this system represented world’s best practice. New Zealand would be well-served by adopting such a protocol for buildings that fall within the higher-risk category.

9 Specialized Building Dispute Resolution in the High Court

- Introduce a specialized building cases list in the High Court, where all building disputes over a certain dollar value must be referred to this division.

- Implement a mandatory mediation mechanism so that shortly after the initiation of legal proceedings, the parties must attend mediation.

- The costs of the mediator would be shared equally between the parties on a 50/50 basis.

- Additionally, ensure that any appeals related to findings or misconduct in building cases by the Building Practitioners Board are heard by this specialized list to maintain consistency and expertise in judgments.

- In forming a best practice construction dispute resolution division, regard can be given to the IBQC Good Practice Guidelines for the Development of Construction Dispute Resolution Tribunals.

10 Product Safety and Compliance

- Establish a national accreditation authority to certify building products, whether local or offshore.

- Create an accreditation mark or stamp to ensure products meet compliance standards and are fit for purpose.

- Avoid the supply of substandard or non-compliant products to enhance the overall quality of construction.

- Adopt the IBQC Product Safety Guidelines for a best practice approach.

Conclusion and Key Takeaways

1 Right-Weight Regulation

- The focus should be on right-weight regulation—neither over-regulation nor under-regulation. The goal is to strike the right balance, ensuring public safety while avoiding excessive regulatory burdens that could hinder industry efficiency.

2 Sustainability of Regulation

- The true measure of good regulation is its sustainability. Effective regulations protect consumers for years while balancing efficiency and safety. Robust regulations endure, while poorly crafted ones can lead to substantial prejudicial impacts for jurisdictions.

3 Avoiding Economic Damage

- When building regulations fail, economic damage is often visited upon the consumer, leading to heightened insolvency activity and impacting the broader economy. Regulatory failure can result in governments having to step in and underwrite the losses. Short-term gains from poorly conceived regulations can escalate into long-term aggravated losses, which increase with the effluxion of time.

4 Adopting International Best Practices and Adopting a Cherry Picking Approach

- A cherry-picking approach should be adopted, selecting the best of the best practices globally. This approach, successfully deployed by the Japanese government in its reforms to building standards law, ensures that New Zealand benefits from proven international strategies. The IBQC guidelines provide a comprehensive resource for cherry-picking the finest elements from good practice in building control systems worldwide, ensuring a holistic and effective regulatory framework.

By adopting these strategies, New Zealand’s building regulatory framework can achieve higher standards of safety, efficiency, and fairness, while remaining sustainable and effective in the long term.

About the Writer

Adjunct Professor Kim Lovegrove , who is admitted to practice in NZ, is a New Zealander who has been involved in law reform for more than 30 years. He was a key figure in the development of the National Model Building Act, which served as the law reform template for several Australian jurisdictions. He also acted as the instructing officer to parliamentary counsel on the development of the Building Act 1993.

He is the Chair of the International Building Quality Centre (IBQC) and is a former senior law reform consultant to the World Bank, where he was deployed to advise reforming jurisdictions in China and Southern Africa, drawing on international best practice approaches. Having been involved in the evolution of building and construction regulation for over three decades, he has studied both successes and failures in New Zealand and abroad.

Disclaimer:

The information provided in this article is for general informational purposes only. It does not constitute legal advice. For specific legal advice related to building regulations and compliance, please consult a qualified construction lawyer.

Image Acknowledgements:

The digital renders used in this article were developed collaboratively by Lovegrove & Cotton and ChatGPT. The photo images that are not the digital renders are stock images sourced from Shutterstock.