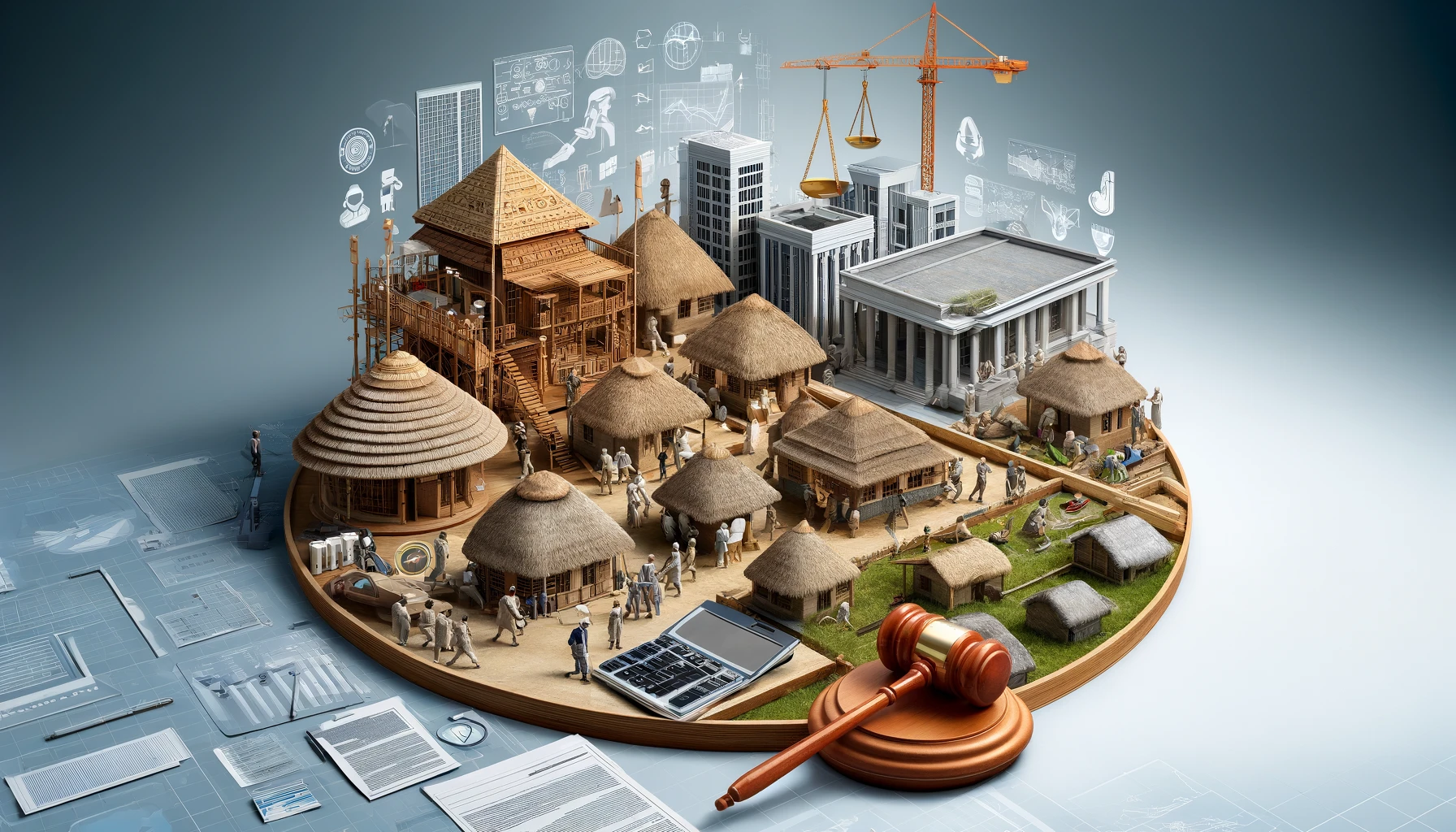

It’s often said that the pen is mightier than the sword.1 This saying is particularly true for statute law, which forms the foundation of a country’s regulatory framework, governing society, institutions, industries, and citizens. Therefore, it is crucial for statute law to be effectively drafted to meet its intended purpose, whether in advanced or emerging economies. This article explores the challenges faced by emerging economies in legislative drafting and highlights best practice approaches to ensure that the legislation is well-crafted and functional.

1. The Power of Effective Legislation

Statute law must accurately reflect the policy intentions of the legislature. Unfortunately, this is not always guaranteed, especially when drafters lack access to specialist legislative drafters. The result can be legislation that, despite good intentions, fails in key areas of its operation.

2. The Role of Parliamentary Counsel

Many developed countries, like New Zealand, the UK, and Australia, have Offices of Parliamentary Counsel (PC). These offices consist of lawyers who specialize in drafting statute law. These experts ensure that legislation is precise and effective, reflecting the intended policy. However, emerging economies often lack such specialized offices due to economic constraints.

3. Challenges in Emerging Economies

Emerging economies may not have civil servants with the necessary legislative drafting skills. Consequently, legislation may be drafted by well-meaning but underqualified civil servants, leading to laws that are not fit for purpose. This can result in statutes that fail to achieve their intended objectives and are dysfunctional in practice.

4. The Swiss Watch Analogy

Well-crafted legislation is like a finely tuned Swiss watch, where all components work seamlessly together. A best practice approach involves appointing a senior civil servant as an instructing officer to parliamentary counsel. This officer prepares comprehensive drafting instructions, which are then used to draft the bill. Multiple drafts may be necessary to ensure the bill accurately reflects the policy before it goes to Cabinet for approval.

5. Importance of Precise Wording

Statutory interpretation relies heavily on the literal rule, meaning the law is interpreted based on its plain wording. If the wording is unclear, judicial interpretation may not achieve the intended result. While legislative amendments can address this, they can be time-consuming and may not always occur.

6. Lessons from Dickens

Charles Dickens once wrote that the ‘law is a ass’3, highlighting that not all laws work as intended. This metaphor underscores the importance of well-drafted laws that consider social realities. Poorly drafted laws can have severe consequences, especially in regimes where citizens must comply with bad laws, leading to negative outcomes.

7. Addressing Resource Constraints

Capacity Building Agencies (CBAs) like NGOs and aid agencies are often reluctant to fund expert legislative drafters due to liability concerns. However, providing such expertise is crucial for ensuring that legislation is fit for purpose. Statutory immunities could address liability concerns, making it safer for CBAs to support the deployment of expert drafters.

8. Regulatory Hierarchy in Building Legislation

In building regulation, confusion often arises between the Act and the Building Code. A best practice regulatory hierarchy involves:

- Building Act

- Building Regulations

- Building Code

The Act should cover administrative provisions, the Regulations should provide detailed criteria, and the Code should address technical matters. This clear demarcation prevents overlap and contradictions, ensuring effective legislation.

9. The Ideal Drafting Team

A best practice drafting team should include:

- A project manager

- Research and development experts

- A legally qualified draftsperson

- A consultative mechanism

- A construction economist

- Coordination with local bureaucracy and key stakeholders

This team ensures that the law is well-drafted, contextualized to the local jurisdiction, and considers the economic impact of regulatory changes.

Key Takeaways

- Effective law reform requires well-drafted legislation.

- If local expertise is lacking, external specialists should be engaged.

- NGOs and CBAs should consider supporting the deployment of expert drafters despite liability concerns.

- A clear regulatory hierarchy prevents confusion and enhances legislative effectiveness.

- An ideal drafting team combines legal, economic, and local expertise to ensure the law is fit for purpose.

Conclusion

The importance of precise and well-crafted legislation cannot be overstated. In advanced economies, dedicated offices of parliamentary counsel ensure that laws accurately reflect policy intentions and are fit for purpose. However, in emerging economies, the lack of such specialized expertise can lead to legislation that fails to achieve its goals. To mitigate this, Capacity Building Agencies (CBAs) should consider providing expert legislative drafters, despite liability concerns, to ensure that laws are effective and enforceable.

A best practice regulatory hierarchy, particularly in building regulation, involves a clear demarcation between the Building Act, Building Regulations, and Building Code. This approach prevents confusion and ensures that each component serves its intended function.

An ideal legislative drafting team should include a project manager, research and development experts, a qualified draftsperson, and a construction economist, working in close coordination with local bureaucracies and stakeholders. This collaborative approach ensures that the law is contextualized and economically feasible.

In conclusion, for emerging economies to achieve effective law reform, it is essential to access the necessary legislative drafting expertise. NGOs and CBAs play a crucial role in this process by supporting the deployment of specialized drafters, ultimately contributing to the creation of legislation that is fit for purpose and sustainable in the long term.

About the writer

Adjunct professor Kim Lovegrove is the founder of Lovegrove & Cotton and is a building regulatory law reform consultant with over 30 years of experience. He was the principal Legal Adviser on the development of the Victorian Building Act 1993 and was co-leader of the team that developed Australian National Model Building Act. Internationally, he has consulted for the World Bank on best practice approaches to the design of building regulations in Mumbai, Shanghai, Beijing, and Tokyo, and was retained by the Japanese government on two occasions to participate in law reform think tanks.

Kim chairs the International Building Quality Centre (IBQC), promoting global best practices in building regulation. He is an Adjunct Professor at the University of Canberra and Southern Cross University, and is a Conjoint Professor at Western Sydney University. His Honours include the Royal Medal of the Lion and the Order of the Star of Honour of Ethiopia.

Disclaimer: The information provided in this article is for general informational purposes only. It is not legal advice. The views expressed in this article are those of the author only and are not to be taken as reflecting the views of any affiliated organizations or entities.

Image Acknowledgements:

The digital renders used in this article were developed collaboratively by Lovegrove & Cotton and ChatGPT. The photo images that are not the digital renders are stock images sourced from Shutterstock.

References

- Edward Bulwer-Lytton, Richelieu; Or the Conspiracy: A Play in Five Acts (second ed), London (1839), p 39.

- Policy to Law, Parliamentary Counsel Office, New Zealand Government (Governmental Website, accessed 21/12/2022) https://policy-to-law.pco.govt.nz/.

- Charles Dickens, Oliver Twist chapter 51, p 489 (1970), first published serially 1837-1839.